Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

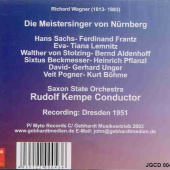

| Rudolf Kempe | |||||

| Chor der Staatsoper Dresden Staatskapelle Dresden | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

| Hans Sachs | Ferdinand Frantz |

| Veit Pogner | Kurt Böhme |

| Kunz Vogelgesang | Johannes Kemter |

| Konrad Nachtigall | Kurt Legner |

| Sixtus Beckmesser | Heinrich Pflanzl |

| Fritz Kothner | Karl Paul |

| Balthasar Zorn | Karl-Heinz Thomann |

| Ulrich Eißlinger | Heinrich Tessmer |

| Augustin Moser | Gerhard Stolze |

| Hermann Ortel | Theo Adam |

| Hans Schwartz | Erich Händel |

| Hans Foltz | Werner Faulhaber |

| Walther von Stolzing | Bernd Aldenhoff |

| David | Gerhard Unger |

| Eva | Tiana Lemnitz |

| Magdalene | Emilie Walter-Sacks |

| Ein Nachtwächter | Werner Faulhaber |

Dresden certainly has a strong tradition of staging Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg with well over five hundred performances since its Dresden première in 1869. Surely there are many more Dresden performances to come as the current principal conductor of the Staatskapelle, Christian Thielemann, now also music director of the Bayreuther Festspiele, is such a Wagner devotee.

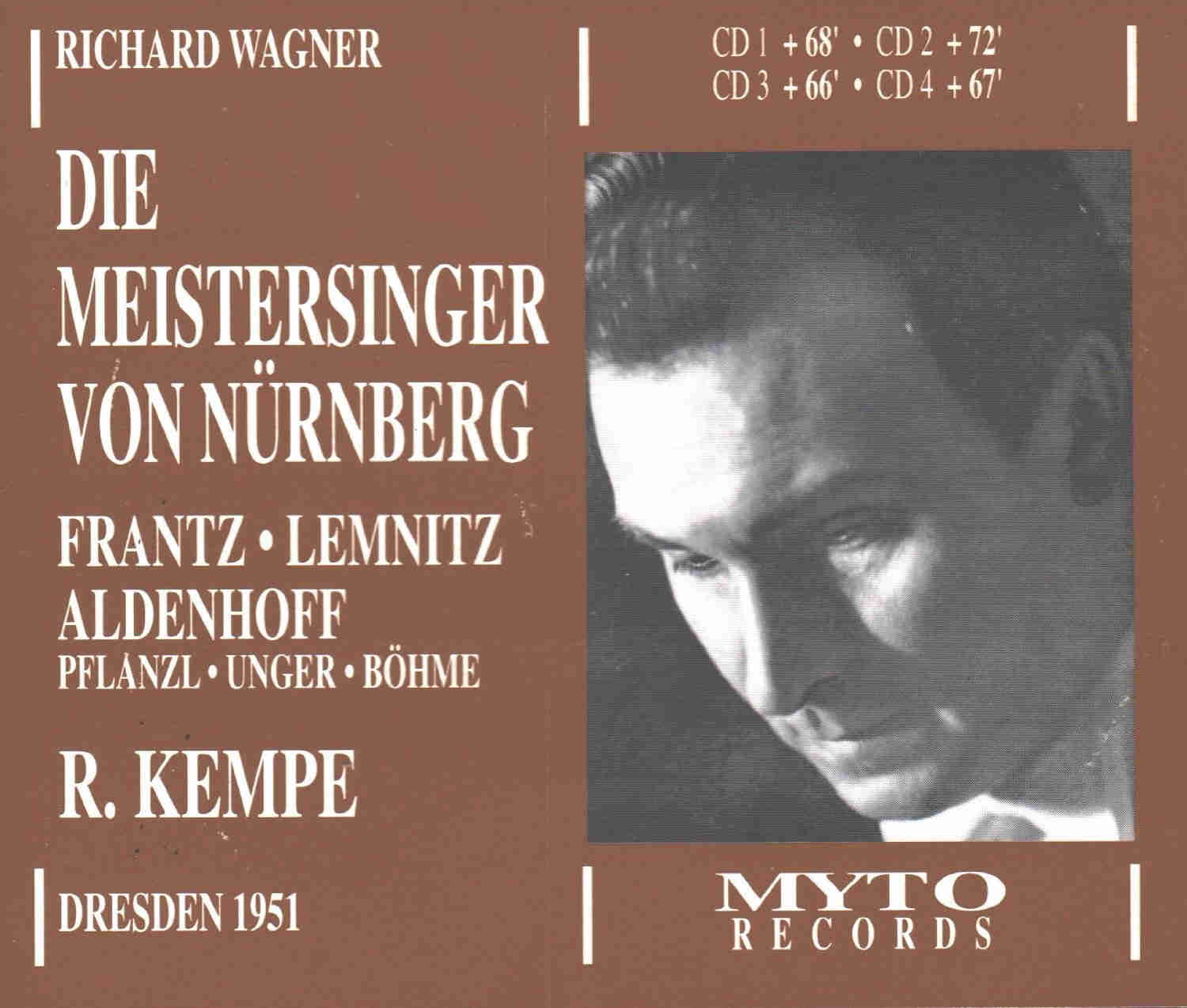

In Dresden, Heinz Arnold’s 1950 production of Die Meistersinger under Rudolf Kempe at Großer Saal, Staatsschauspiel, was highly successful. So it was decided that the Dresden broadcasting station of Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk would record under studio conditions Kempe’s complete Die Meistersinger. With the exception of Ferdinand Frantz as Sachs and Tiana Lemnitz as Eva the cast is largely the same. The recording was made on 29 April 1951 in Dresden at either the Großer Saal, Staatsschauspiel, which after 1945 bomb damage had reopened in 1948 or the Steinsaal des Dresdner Hygienemuseums that was being used by the Dresden station as a recording studio. Wagner had three operas premièred at the Semperoper which is where this recording would probably have been made but bombing had virtually destroyed the building which was undergoing reconstruction until 1985. Lasting almost 4½ hours this 1951 recording has been produced using the original master tapes, actually 19 magnetic tape spools that had been discovered in storage at the Berliner Rundfunk Forschungszentrum where they had been since the late 1950s. The masters have now been returned to Dresden and are archived at Sächsischen Landesbibliothek.

Turning his attention temporarily away from Teutonic mythology, Wagner’s lifelong obsession, he chose a comic opera for his next project. As a teenager Wagner had seen the play Hans Sachs by Johann Ludwig Franz Deinhardstein in Vienna. Further inspiration came from reading Georg Gottfried Gervinus’s book on the history of German national literature, Johann Christoph Wagenseil’s commentary on the noble art of the Mastersingers of Nürnberg. In 1842 he attended a performance of Lortzing’s opera Hans Sachs at Dresden. Wagner’s idealised setting is a thriving community in medieval Nürnberg with its numerous trade guild societies of which the Meistersingers is the most distinguished. It’s a comedy, a predominantly sunlit score although there are some sinister moments and it concludes with irrepressible affirmation and celebration.

Deservedly stealing the show on this recording for his performance of cobbler Hans Sachs is Kassel-born bass-baritone Ferdinand Frantz. A renowned Wagnerian, especially noted for the roles of Wotan and Sachs at the time of this recording, he was a member of the Bayerische Staatsoper. Frantz’s undoubted vocal authority, clarity of enunciation and resilience in this long and demanding role are palpable. He doesn’t put a foot wrong. In Sachs’ act 2 Flieder Monologue and act 3 Wahn Monologue Frantz’s rounded, mahogany tone is displayed to great effect anchored by his substantial and firm, low register. Especially agreeable is the act 2 Cobbler’s Song and the act 3 Verachtet mir die Meister nicht in praise of holy German art. The latter immediately precedes the triumphant closing chorus. In her prime Tiana Lemnitz’s portrayal of Eva, Pogner’s daughter, a signature role was much acclaimed. A member of the Staatsoper Berlin from 1934 for over twenty years the Metz-born soprano, who would have been in her mid-fifties for this recording, sings with assurance as a suitably girl-like Eva. A highlight is Eva’s act 3 aria O Sachs! Mein Freund, with Lemnitz’s radiant, fluid voice communicating blissful happiness. She achieves her high notes comfortably.

In the role of Walther von Stolzing, the young knight from Franconia is the Duisburg heldentenor Bernd Aldenhoff. Renowned as a poised and sensitive Wagnerian Aldenhoff was at the time of this recording a Staatsoper Dresden member. Later in the season he played his first Siegfried at the Bayreuther Festspiele. Walther’s testing Prize Song from act 3, a love song to Eva, is rendered impressively by Aldenhoff. Not over-bright his voice, with splendidly clear diction, has a deceptive tensile strength and can reach down to a near baritonal level. Aged around 35 at the time of this recording Gerhard Unger’s voice easily passes for Sachs’s young apprentice David which was a signature role for him. From Bad Salzungen the lyric tenor was at the time with the Staatsoper Dresden. He was starting to appear regularly at the Bayreuther Festspiele and later became a Staatsoper Berlin member. Making the most of his role Unger is especially admirable in Schumacherei und Poeterei from act 1. His attractive voice, reasonably bright but not piercing, displays ample sincerity and musicianship.

The opera’s often discussed disturbing undertow revolves around the Jewish caricature of Sixtus Beckmesser, town clerk and chief marker of the guild, who is subsequently held up to mockery and disgrace. Singing Beckmesser is Salzburgian Heinrich Pflanzl who was that season to sing Beckmesser, Kothner and Alberich at Bayreuth and was around this time attached to the Komische Oper and Staatsoper Berlin. From act 2 Beckmesser Serenade: Den Tag seh’ ich erscheinen the town clerk is beneath Eva’s window ridiculously singing of his excitement at the possibility of winning Eva in the song contest. Pflanzl’s fluid voice is immediately noticeable in the Serenade, eminently expressive and well controlled too.

Kurt Böhme sings the part of Veit Pogner the goldsmith. From act 1 in Pogner’s Monologue: Das schöne Fest, Johannistag the goldsmith is looking forward to tomorrow’s singing contest and will give his daughter Eva away as the song contest prize. The Dresden-born bass who had been a member of Staatsoper Dresden was at the time part of the Bayerische Staatsoper and would later sing Pogner at the Bayreuther Festspiele and join the Wiener Staatsoper. Mature sounding, Böhme’s voice is reasonably steady and here he maintains a dark tone throughout. The role of baker Fritz Kothner is taken by Karl Paul a native of Crimmitschau, Saxony. Formerly at the Staatskapelle Weimar, at this time the baritone had recently joined the Staatsoper Dresden. In Was euch zum Leide Richt from act 1 the baker is reading out the competition rules to Walther and the design the song must take. Making his mark, Paul is well focused and provides good expression and colouration. Another highlight is the celebrated act 3 quintet Selig, wie die Sonne beautifully performed and decidedly affecting too.

With consistently attractive playing from the Staatskapelle, Rudolf Kempe successfully balances the broad dynamics with the melodic line. As the pinnacle of the evening the conclusion exceeds its reputation. The vocally inspiring choral forces of the Staatsoper sing their hearts out in praise of Hans Sachs the Meistersinger of Nürnberg. It is one of those special spine-tingling operatic moments.

Accompanying the Profil release is a lavishly presented 84 page booklet. It provides detailed notes that serve as a synopsis, biographies and a number of fascinating photographs. The images used are mainly from the Dresden productions directed by Heinz Arnold from 1950 and the Wolfgang Wagner in 1985. Sadly a black mark has to be awarded for not providing a libretto and translations; indispensable for opera releases. Re-mastered in 2013 from the original Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk tapes by THS Studio Holger Siedler the 65 year old sound of the soloists has a remarkable clarity, the orchestra rather less so. Noticeably the producer has the soloists placed appreciably forward of the orchestra something that I don’t often experience with many recordings today but an approach definitely to my taste.

The two recordings of Die Meistersinger that have provided the most satisfaction over the years are from Eugen Jochum and Rafael Kubelik. Jochum directs the Chor und Orchester der Deutschen Oper, Berlin with Sachs played by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau Sachs and Catarina Ligendza as Eva. This was recorded by DG in 1976 at the Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin. Then there’s Rafael Kubelik and the Chor und Sinfonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks with Thomas Stewart in the role of Sachs and Gundula Janowitz as Eva from 1967 at Herkulessaal, Munich. This was re-mastered on Arts Archives but had originally been released on Calig.

The present epic Dresden performance from Kempe is the finest I have heard. We hear a tremendously balanced cast singing with a spontaneous quality that one rarely encounters in studio recordings. In short this is a Meistersinger to treasure.

Michael Cookson

AUS EINEM GUSS

Neu sind diese Meistersinger von Nürnberg nicht. Neu ist der Rückgriff auf die Originalbänder. Und das zählt. Erstmals dürften sie bei Vox herausgekommen sein, noch als LP-Kassette. Später dann auf CD bei Myto. Als MP3 liegen sie bei Cantus vor. Der Klang war so schlecht nicht. Jetzt nahm sich Profil Edition Günter Hänssler die Rundfunkproduktion von 1951 im Rahmen der Semperoper Edition vor (PH 13006). Es hat sich gelohnt. Alles, was bisher zu hören war, wird auf die hinteren Plätze verwiesen. Die Aufnahme wird in ihre alten Rechte eingesetzt. Sie klingt transparent und klar. Wie am ersten Tag. Vielleicht noch besser. Insofern kann sie es technisch mit vielen Produktionen aus späteren Jahren aufnehmen. Stimmlich sowieso.

Vom ersten Ton an wird orchestrale Pracht entfaltet. Die Zuhörer werden regelrecht hineingezogen in das Wer. Der Eindruck ist so stark, dass man zuletzt darüber nachdenkt, in welchem Jahr die Aufnahme denn eigentlich entstand. Wirklich schon vor 65 Jahren? Ist das kein Irrtum? Ist es nicht. Einmal schleift das Band während des Vorspiels. Wie bei einem Spulengerät, das im Begriffe ist, seinen Geist aufzugeben. Nanu? In diesem Moment kommt eine Ahnung vom tatsächliche Alter auf. Für diesen kurzen Moment. Als würde ein Schleier gelüftet. Schnell ist es vorbei. Die Musik gewinnt ihr Tempo zurück. Was sich in den nächsten Stunden im Orchester abspielt, macht Zeitrechnungen nebensächlich.

Am Pult der Staatskapelle Dresden steht Rudolf Kempe, der fünf Jahre später Wagners Meistersinger erneut für die EMI einspielte. Kempe war zum damals Generalmusikdirektor der Dresdner Staatsoper. Aufgenommen wurde in Mono. Während bei der Stereophonie ein räumlicher Eindruck durch mehrere Schallquellen erzeugt wird, schafft er es durch Fertigkeit – und Kunst. Ob Streicher, Holz, Blech oder Pauken. Kempe gewährt den einzelnen Instrumentengruppen viele solistisch anmutende Entfaltungsmöglichkeiten. Sie treten an den entsprechenden Stellen jeweils deutlich hervor, fallen aber nie auseinander, weil mit Kempe ein Kapellmeister vor ihnen steht, der alles lenkt und den großen Apparat mit fester Hand zusammenhält. Dadurch entsteht mitunter ein Höreindruck, der an ein frühes Stereo erinnert. Ein großer Vorzug der Aufnahmen ist das. Es wird deutlich, dass kein noch so perfekt ausgeklügeltes Aufnahmeverfahren ersetzen kann, was dem Dirigenten zukommt. Er befindet über die musikalische Qualität und nicht der Toningenieur.Mehr als die Musiker sind es die Sänger, die dieser Produktion den historischen Touch aufdrücken. So wie sie singen, singt heute keiner mehr. Wissend und stets dem Wort verpflichtet. Immer ist alles zu verstehen. Wer den Text nicht kennt, könnte ihn anhand dieser Aufnahmen, die übrigens die erste Studioproduktion dieser Oper gewesen ist, auswendig lernen. Ideale Voraussetzungen dafür sind dadurch gegeben, dass alle Mitwirkenden deutscher Zunge sind. Sie haben gut gelernt, sind mit ihren Rollen oft seit Jahren vertraut, haben sie unter den verschiedensten Bedingungen und Dirigenten ausprobiert. Nichts wackelt. Die Bälle fliegen hin und her. Bühnenatmosphäre kann nicht anders sein. Oder sind diese Meistersinger von Nürnberg auch deshalb wie aus einem Guss, weil sie an nur einem einzigen Tage, nämlich am 29. April 1951 eingespielt wurden?

Fast alle Sänger sind in den besten Jahren für ihre Partien. Ferdinand Frantz, der den Hans Sachs gibt, wurde 1906 geboren, ist zum Zeitpunkt der Produktion Mitte vierzig. Er singt den Schuster sehr geschmeidig. Bernd Aldenhoff, als Stolzing etwas hart im Ton, und der stimmgewaltige Kurt Böhme (Pogner) sind Jahrgang 1908, die Eva Tiana Lemnitz 1897. Sie ist Älteste im Ensemble, was auch zu hören ist, hat ihren Zenit deutlich überschritten und kann die “Jungfer” nicht mehr überzeugend darstellen. Die Lemnitz rettet sich mit all ihrer Erfahrung entschlossen in die Kunst. Sie zelebriert die Figur, macht hohe Schule daraus, statt sie mit wirklichem Leben zu erfüllen. Schade, dass nicht die 1913 geborene Elfride Trötschel besetzt worden ist, die die Eva zur gleichen Zeit mit großem Erfolg in Dresden auf der Bühne sang.

Einige Namen auf der Besetzungsliste stehen für das Kommende. Der 1916 geborene Gerhard Unger hatte erst nach dem Krieg begonnen. Er ist ein idealer David, wirbelt jungenhaft, selbstbewusst und umtriebig durch die Produktion. Kein Wunder, dass ihn Kempe auch bei seiner zweiten Studioeinspielungen einsetzte. Aus seiner großen Szene im ersten Aufzug, wenn er dem Walther von Stolzing Sinn und Zweck des Meistergesangs erklärt, wird ein Kabinettstück ohnegleichen Theo Adam, Jahrgang 1926, später selbst ein bedeutender Sachs, sammelte erste Wagner-Erfahrungen als Seifensieder Hermann Ortel. Der gleichaltrige Gerhard Stolze, der es als Mime zu Weltruhm brachte, sang den Augustin Moser. Und die große Dresdner Bariton-Hoffnung Werner Faulhaber, der nur ein Jahr jünger war und 1953 tödlich verunglückte, ist mit zwei Rollen, Hans Foltz und Nachtwächter, vertreten. Um ihn ist es wirklich schade. Er hätte dem Operleben noch sehr viel geben können.

Rüdiger Winter