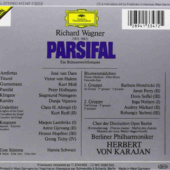

Parsifal

| Amfortas | José van Dam |

| Titurel | Victor von Halem |

| Gurnemanz | Kurt Moll |

| Parsifal | Peter Hofmann |

| Klingsor | Siegmund Nimsgern |

| Kundry | Dunja Vejzović |

| Gralsritter | Claes H. Ahnsjö |

| Kurt Rydl |

When Herbert von Karajan initiated his Salzburg Easter Festival in 1967, it was his plan that each new opera production would first be prepared musically to festival standard and recorded, afterwards rehearsed on stage with the recorded tape as accompaniment, whenever desirable for purposes of timing, placing, or whatever –singers could learn their moves without having to sing at the same time, and producer Karajan would not have to conduct until final rehearsals. There was for festival subscribers the extra advantage that, on collecting their tickets, they would receive also the boxed set of records relevant to the year, some months before the ordinary record-buying public had access to it.

Last year’s opera was Parsifal, the perfect work for a festival that includes Good Friday in its schedule, but one that Karajan had never before produced nor conducted since his prentice years, if then. For one reason or another, he had let it be known, from the first, that he was not in a hurry to bring Parsifal to his Easter Festival, but in 1980 he was ready, and by the time his production took the stage, the music had already been taped in the Philharmonie, Berlin, with DG’s Gunther Breest as record producer, during December 1979 and January 1980. The finished pressings were not ready by Easter (we were given Beethoven’s Triple Concerto instead), but here they are now, in time for the 1981 Salzburg Easter Festival which includes a revival of Parsifal.

Greatly though I admire Karajan as a Wagner conductor, I had some reservations about the musical performance of Parsifal at Salzburg last year. Wagner composed it expressly for an opera house with a sunken, hooded orchestra pit, namely his own, virtually handmade Festspielhaus at Bayreuth where the musical balance between stage and pit is ideal. In the large Festspielhaus at Salzburg, every spectator sees the entire orchestra and its conductor. Karajan made no attempt to reduce the decibel content of Wagner’s forte and fortissimo, so the singers’ words, sometimes their tone also, were often swamped, even such a big voice as Kurt Moll’s.

The records are another matter. Great pains have evidently been taken about balance, and indeed about the acoustic character of each scene. The orchestral music sounds miraculously clear and clean and beautiful, with all the inner detail for violas and bassoons and third horn, etc, that the keenest student could wish – doubtless the digital recording technique helped here. The first trumpet solo in the Prelude sounds to me even one notch too loud. There is a magical stillness in the music when Gurnemanz questions Parsifal (‘Das weiss ich nicht’ always the answer) then, in the transformation interlude, orchestral note-values and rhythms are minutely detailed, even on double-basses. Once arrived in the temple, we hear an indoor acoustic when Gurnemanz sings ‘Nun achte wohl’. The chorus of Knights approaches from a cavernous distance, and departs with similar theatrical effect at the end of Act 1.

A stunning acoustical coup occurs at the beginning of the Flower-maidens’ waltz ensemble, the soloists heard close at hand, the chorus farther away, subdued yet distinct. The Good Friday Magic music is exquisitely balanced and weighted and coloured, the transformation to Titurel’s funeral cortege again treated as aural spectacle, the bells now prominent as, before, the stage drums and orchestral bass shudders sounded. The scrupulous voice/orchestra balance does falter in the later part of the seduction scene, after Kundry’s account of Christ’s Via dolorosa, when several times the voices dominate the orchestra excessively.

I am trying to unburden my reservations first, because the new set is, taken all round, so nobly and euphoniously imagined and realized. In the first scene Karajan’s view may sound so intent on the perfection of sound-quality as to forget the element of rough humanity which, after all, Parsifal is about: the untamed vitality, heedless and unconsidering, of the name-part, the emotional dichtomy of Kundry, the malignity of Klingsor, the self-pitying outbursts of tormented Amfortas, Gurnemanz’s moments of bad temper – even he isn’t a perfect goody-goody. Karajan does elsewhere take this element into account. Much of the second act music is propelled with a bouncing vigour, strongly paced and excitable, that may cause surprise to those of us brought up on the Decca Knappertsbusch set of 1951 (3/52); I certainly raised an eyebrow or so, only to decide that Karajan was justified, even if his singers were encouraged to force the tone, and accordingly lose tonal steadiness.

In the prelude to the third act, the first two fortepiano accents (strings alone) bring you up with a jolt, they are so strong so early in the piece: surely a gentler dig at the chords would benefit the flow of the music? But the prelude is about Parsifal’s years of wandering – hence the tonally uncommitted harmony and the burdensome nature of those accents whenever their theme occurs: I don’t like them, but they aren’t wrong in the context. Similarly, in firmly measured music like this (4/4) I’m upset by a conductor who anticipates the next bar’s downbeat, as Karajan often does; but this is the music of a wandering pilgrim, and Wagner has given the lead by often tying the strong beat over to the bar before. There are, of course, some examples of that Karajan speciality, the perfectly unanimous orchestral chord that has been allowed deliberately to slacken, rather as old-fashioned pianists used to play left hand before right, as if it were an arpeggio – Karajan does it more sophisticatedly. I won’t pretend to justify one blatant lapse of ensemble (oboe and cor anglais – I won’t reveal where) except that ‘To err is human, to forgive divine’.

One can forgive plenty within earshot of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the chorus of the Berlin German Opera (what used to be the Charlottenburg house in Richard Strauss’s day) who sound as resplendent here as did the four choruses from Salzburg, Vienna, and Tolz in the Easter Festival performances. The singing, and placing, of the choral groups in the Holy Communion scene have nothing to yield to those in the Decca/Solti or Philips/Knappertsbusch sets. Their work is crowned, at the end of Act 1, with Hanna Schwarz’s memorable account of the clinching phrase, brief and absolutely vital for the validity of the whole performance.

The casting remains on that level, with Barbara Hendricks as leader of the Flower-maidens, and Claes H Ahnsjö as first Knight, international stars of great repute. The finest of all the principal singers is surely the Gurnemanz of Kurt Moll, a wonderful blend of bel canto and Lieder singing, the voice a true bass, perfectly poised and projected, finely nuanced, ever attentive to the colour and meaning of words, witness his monologue about Amfortas’s loss of the holy spear. His equal would be José van Dam as Amfortas, but for some lapses of pronunciation in the final scene; earlier his vivid words have matched the strong, expressive, keenly focused voice, truly a basso cantante with a remarkable baritone upper extension. His gruelling monologue, ‘Wehvolles Erben’, which has worried so many opera-goers for 98 years, is sung with a dignity to be admired, not admonished, and his slow downward portamento (to call it a slither would give the wrong impression) is exquisitely moving. Titurel sounds, paradoxically but truthfully, firm and infirm, an old man still a fine singer. The Klingsor, Siegmund Nimsgern, suggests the spiritual conflict of idealism turned to spite, without reminding one of Gounod’s Mephistopheles.

The Kundry is Dunja Vejzovic, basically an alto with an uneasy but exciting upper extension, rather like Martha Mödl, great Kundry of the early 1950s, but more sharply projected. It seems that Karajan coached her in the part for a whole year. Her soft singing is naturally lovely, loud and low as well as high and mezza voce. She manages the huge downward leap at ‘und lachte’ (she mocked Christ bearing the Cross) very cleanly, but expert as a technical rather than musical feat. Her upper register is inclined to sprawl, though she takes the final, unauthentic top B securely. The music is always ably negotiated, only sometimes voiced as a consistent character, probably the most interesting in any Wagner opera. Peter Hofmann, such a good Parsifal, young, stupid, saintly, ultimately responsible, projects the part less acutely on record than on stage – the microphone catches the edge in his voice and the forced unsteadiness, not the round, virile ring that looks back to Melchior. The singing, as such, is sensitive and expert, by any standards.

In most respects this is the most perfect, atmospheric Parsifal yet committed to disc. Admitting the vocal imperfections, few as they are, the set attempts an artistic, or at least technical superiority which it fairly achieves. The Philips/Knappertsbusch has a magical atmosphere, in which only its Decca predecessor (also conducted by Knappertsbusch) excelled, and then not in stereo. Both contain great performances, such as Hotter’s Gurnemanz, (Weber’s on the 1951 set), Mödl’s Kundry, Uhde’s Klingsor.

The Decca/Solti set has a rougher, more urgent sound which contrasts violently with the infinite, almost aseptic sound of Karajan. As in his Salzburg Ring set, Karajan opts for a subdued, chamber-musical style whenever possible, favouring voices and words. Solti, a greyhound to Karajan’s Siamese, chases the innards of the music to expose them, takes risks, but has the spirit of the score always in his blood, where Karajan perhaps looks for its transcendental spirit. Whether either of them is a practising Christian means nothing: who understands the whole contents of Parsifal, and projects it all? I admire both sets. They are to me, at present, like Keats’s dichotomy: the Karajan is Beauty, the Solti is Truth. If that is far from all any of us knows, or needs to know, I will settle just now, for Beauty, having spent a car journey to Wales and back revelling in, and learning from, Karajan’s set again in its, clear, richly atmospheric, cassette form.