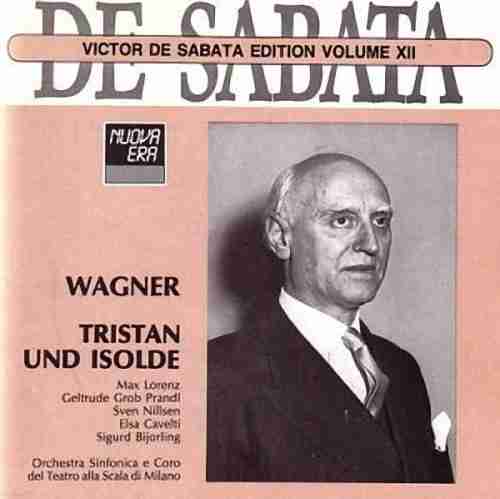

Tristan und Isolde

| Victor de Sabata | |||||

| Coro e Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala Milano | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

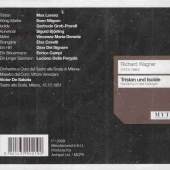

| Tristan | Max Lorenz |

| Isolde | Gertrude Grob-Prandl |

| Brangäne | Elsa Cavelti |

| Kurwenal | Sigurd Björling |

| König Marke | Sven Nilsson |

| Melot | Vincenzo M. Demetz |

| Ein junger Seemann | Gino del Signore |

| Ein Hirt | Luciano Della Pergola |

| Steuermann | Paolo Montarsolo |

This famous recording of Tristan und Isolde has long been unavailable having first appeared on LP in 1978 and then on CD in 1989, both times on Italian labels, and both times hastily deleted. This new release on Archipel returns it to the catalogue where it takes its place as one of the most searing performances ever made of this opera. Even given the quite appalling sound – which requires considerable tolerance – it is easy to hear how de Sabata, that most electrifying of conductors, whips his orchestra into a veritable whirlwind of sound; only Böhm, at Orange, and Karajan at Bayreuth equal him. His cast might not match in matters of detail that of other conductors (the rather tame Leinsdorf with Melchior and Traubel (1943), for example), but the intensity with which they sing their roles is as satisfying as any on record.

De Sabata’s approach to this opera remained largely unchanged over the years he conducted it: he was always blistering, it seems, the most fiery of interpreters in an opera that benefits from such an approach, although it is by no means the only one. A December 1930 set of excerpts (mostly from Act III, and sung in Italian) has frightening passion as do more extensive excerpts from a fabled 1948 performance at La Scala (not yet released on CD) in which his Tristan was Max Lorenz and his Isolde Kirsten Flagstad. This performance (which includes the Act I prelude) again preserves only Act III excerpts but includes an incandescent reading of the Liebestod. Listen to the fragments from a 1947 La Scala performance (on Minerva MN-A54), although possibly of questionable authenticity (at least in terms of the date), and there is a similar structural integrity. Its value, however, is in giving us extracts from Act I which is otherwise only represented on disc in this release, the most complete performance of a de Sabata Tristan we have (although it is extensively cut – see below).

His approach to the Prelude changed very little, too. His 1938 Berlin Philharmonic version is volatile, as is a New York Philharmonic performance from 1955 (on Arkadia), both sweeping incandescently to a voluptuous climax (contrast this with his dull approach to the Parsifal Act I prelude). Celibidache, who sneaked into rehearsals of de Sabata rehearsing this Tristan at La Scala, was clearly influenced by this approach: the single recording we have of him conducting the Prelude matches de Sabata’s symmetrical line – albeit at a slower tempo. This approach, however, which gives the climax from bars 72 – 85 an unwritten accelerando, is something which Wagner interpreters all but take for granted as being the norm. Böhm is a classic example and follows de Sabata’s model extremely closely. It is an undeniably expressive approach, and de Sabata’s performance of the entire opera is focused to achieve a surging magnetism, but at the expense of the tension which this opera sometimes requires. Wagner does not specify a single change of tempo during the prolonged ascent to the climax, and only a slight holding back thereafter. Turn to Bernstein on his intense and very long performance with the magnificent Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and you have the ideal, at least in terms of orchestral playing (the singing can leave a lot to be desired). This is the closest on record you will ever get to hearing the Prelude exactly as it is written to be played, or as Karl Böhm said of hearing Bernstein rehearsing the Act I Prelude, “You dare to play this music as Wagner wrote it”.

De Sabata’s Isolde is Gertrude Grob-Prandl, an incandescent Brunnhilde in a 1949 Vienna Ring Cycle conducted by Rudolf Moralt (and still available on Gebhardt, and well worth hearing). If she lacks the sheer physicality and emotional presence of Flagstad it is partly because she adopts a much younger and fresher approach to the role. There is petulance in her singing, and when she comes to the curse she is overly dogmatic (not to say phlegmatic) in her delivery. She, like her Tristan, Max Lorenz, have some problems in Act II which de Sabata takes at astonishing speed. The wildness of the conducting is breathtaking, but his singers are all but dissolved like dust into the resulting maelstrom. The passion is headstrong, but at such a speed, and with such drastic cuts, the act loses its architecture. In Act III Lorenz reaches staggering heights of rage and madness (much as Vickers does on Karajan’s hideous studio recording), but again it is de Sabata and his inspired orchestra which give the greatest pleasure. The playing, if shaky, is stunning at conveying the inner angst and passion which describes Tristan’s despair, and go to the beginning of the act to hear an Act III Prelude which is amongst the most tragic ever heard on record.

The cuts are extensive, more so than on any of the leading recordings for a great Tristan (Böhm, from Orange, for example, makes only the standard Act II, scene 2 cut). In Act I, the most fluid and intemperate of the three under de Sabata’s baton, there are two: in scene 5, from “Muh’t Euch die?” to “warum ich dich da nicht schlug” and from “Geletest du mich” to “..zu sühnen alle schuld”. Act II suffers the most (and Sven Nilsson as King Marke sings much less than he should). This is by far the shortest Act II on disc (and would have been so without these cuts given de Sabata’s wild tempo). The cuts are in scene 2 from “Dem Tage! Dem Tage!” to “dass nachtsichtig meain Auge..”, from “Tag und Tod mit glecihen” to “ewig ihr nur zu leben” and in scene 3 from “Wozu die Dienste ohne Zahl!” to “Da liess er’s denn so sein” and from “Nun, da durch solchen Besitz” to “meiner Ehren Ende erreiche”. In Act III scene 1 there are cuts from “Isolde noch im Reich…” to “die selbst Nachts von ihr mich scheuchte”, from “Muss ich dich…” to “Zu welchem Los” and finally from “Die nie erstribt” to “Der Trank! Der Trank!..”.

This is without doubt the most searing Tristan on record, and for that reason it is indispensable (because so many are not). When I first heard it as a young boy in the late 1970s it overwhelmed me and I still feel a sense of shock when hearing it today – particularly Act II which still has the power to devastate. Today, there is much to compare with it – the Böhm from 1973, the Bayreuth Karajan, the 1948 Erich Kleiber and a few other performances which I will cover in my survey of Tristan on record, to be published in February. It is the antithesis of the infamous (but undeniably great) Bernstein performance, and readers who know only that recording (surely very few) will be shocked by the differences. At bargain price, the de Sabata should be in every collection –a desert island Tristan, but one only for a desert island.

Marc Bridle

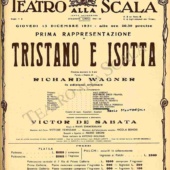

This recording of Tristan und Isolde, taken from a La Scala broadcast on 13 December 1951, is an important issue on several counts. To my knowledge, it’s the only extant complete Wagner performance conducted by the legendary Victor de Sabata, whose discography, though admired, is comparatively small. It also restores to the catalogue a version of Tristan that ranks, in my opinion, among the finest preserved in sound. This is not, I hasten to add, a view universally shared, though other assessments of the recording have been few and far between.

Though de Sabata was rated by such greats as Ernest Newman as one of the finest of all Wagner conductors, his achievement here has tended to be sidelined. Availability has doubtless been one factor in the recording’s neglect: Melodram first issued it on vinyl in the late ’seventies, though it was soon dropped from its catalogue; this marks its first appearance on CD. The date and place of the performance may have been another contributory factor. Discussions of Wagner performances in the early ’fifties tend, with the exception of Furtwangler’s famous ’Ring’, to be focused not on La Scala, but on the post-war re-opening of Bayreuth in 1951. Other important Tristans around the time have also tended to hog the critical limelight, notably Karajan’s 1952 Bayreuth performance (still hotly discussed and now on Myto), and, of course, Furtwangler’s epoch-making EMI version issued the following year.

Victor de Sabata’s recording also brings a number of problems in its wake, on which its detractors have always leapt and which must be mentioned before going on to assess its strengths. First of all, the sound, even by the standards of the period, is variable – restricted if acceptable in the first two acts, though with Act III notably marked by a rapidly increasing level of distortion that sets in some twenty minutes into its course. The Archipel re-mastering is unquestionably impressive. Most of the awkward tape joins that marred the Melodram issue have been smoothed out. Some distortion has been eliminated, though there are still stretches in both Tristan’s delirium and the ’Liebestod’ that require extreme patience. The second problem concerns the cuts, which are extensive. In addition to the standard snips in the first half of the love duet and Tristan’s Act III monologue, de Sabata made further excisions in the lovers’ Act I confrontation, the second half of the love duet and King Mark’s monologue in Act II, and several passages between Tristan’s death and the Liebestod in Act III.

His reasons for doing so are undocumented though they don’t seem to have been made to ease the vocal burden of any one specific singer. Against these drawbacks must, however, be set the devastating impact of the performance, which is characterised by a daunting momentum, a deceptive use of tempo and pace and by De Sabata’s (in my opinion) unequalled ability to integrate fine points of detail into the whole. One of the main ideas behind the work is that the lovers’ inexhaustible and unquenchable desire for each other finds expression in music that is never melodically or harmonically still, and here the sense of restless energy, the convulsive ebb and flow of emotion, is all-pervasive. The whole progresses in a single, relentless, erotic span, in which the tension never slips for a moment. The ’white heat’ – a critical commonplace used in describing de Sabata’s conducting in general – is very much in evidence in every bar.

Yet the unremitting propulsion is deceptive. Just as Wagner deems the phenomenal world in which the lovers are trapped to be illusory, so de Sabata presents us with a soundscape in which tempo and pace are unnervingly at odds with one another. The first act, shrill with hysteria and repression, is seemingly taken at breakneck speed, though de Sabata is actually slower throughout than Karajan, Furtwangler or Reiner, all of whom come over as less edgy and more spacious. The opposite effect occurs in the love duet, where, in the string passage after Brangane’s call from the watchtower, de Sabata appears to bring the score almost to a standstill, though he’s faster here than Bohm, who seems infinitely more urgent at this point.

The wealth of detail embedded in the sonic tapestry is astonishing too. Open the score at any point and you will find Wagner’s expressive instructions obeyed to the letter without a single interruption to the onward flow. In the Act I ’Prelude’, the differentiation between ’belebend’ (being stimulated – the connotation is predictably erotic), ’belebt’ (stimulated) and ’zart’ (tender) is meticulously observed. Turn to Isolde’s memory of looking into Tristan’s eyes and you find the instruction ’sehr ausdruckvoll und zart’ (very expressive and tender) – and that is precisely what you hear. At the opening of the fast section of the love duet, de Sabata seems to allow the tempi to career all over the place instead of holding the beat steady – though this is comparably true to the score where we find Wagner requesting the conductor to ’follow the expression depending upon whether it is fiery or tender’.

Textures are all phenomenally dealt with, as well. It’s a measure of de Sabata’s genius that so much orchestral detail is apparent given the restricted sound. His approach here is essentially forward-looking, aligning Wagner with his effective successors, whether willing or not. A Debussyian delicacy underpins Brangane’s warnings. There’s a Straussian glow in the basic orchestral sound. A single moment of ragged ensemble apart (at the start of Act II), the playing is magnificent, with the La Scala strings at once sumptuous and staggeringly accurate, the woodwind warm and reflective, the brass very vibrant.

The singing is variable though the best of it is stamped with greatness. Another factor that may have mitigated the recording’s wider circulation is the absence of obvious ’star’ Wagnerians in the cast, with the exception of Max Lorenz, who, ironically, gives the weakest vocal performance. A natural Siegfried with a big, clarion Heldentenor voice, he never quite possessed the ability to sustain an extended legato line at pianissimo – qualities that are necessary for Tristan if the love duet is to work ideally. By 1951, Lorenz was nearing the end of his career and gravitating towards roles such as Herod. His voice had developed a beat, which sometimes widened into a spread that pulled him off pitch. You’re also aware that he’s ’saving himself’ for Act III, where he characterises Tristan’s ravings with considerable force, even if he’s prone to bark in places.

His Isolde is Gertrude Grob-Prandl, a singer respected if not idolised in her day, though of late there has been a considerable revival of interest in her work. She appeared on the scene at a time when the great Wagnerian vocalists (Flagstad, Traubel) were beginning to be eclipsed by outstanding singing actresses (Modl, Varnay), and to a certain extent she embodies the approach of both schools. The voice itself stuns, though it possesses qualities unique and unusual in Wagner – a cuttingly penetrative quality rather than comfortable amplitude, and astonishingly vibrant upper registers, even though the tone quality diminishes low on the stave or beneath it. There are moments – particularly in the Act I confrontation with Tristan – where you become aware that Wagner’s vocal writing lies awkwardly. Her dramatic commitment is never for a second in doubt, however. Her scorn and rage in Act I are terrifying. Isolde’s curse seems wrenched from her with terrible fury (the high notes are simply electrifying). Once past the drinking of the potion, her singing is characterised by an easy, flowing, ecstatic quality at once erotic and mystical. There’s no doubt about her stamina too – despite the wretched sound by the time we get to the ’Liebestod’ you can still hear her voice riding the orchestra with sumptuous ease.

The rest of the cast is equally outstanding. Elsa Cavelti is the most human and sensitive of Branganes, rapturous and sexy in her call from the watchtower. The Kurwenal, Sigurd Bjorling (he had sung Wotan at Bayreuth the previous summer), is velvet-voiced, supremely beautiful and passionate – so much so that you’re left wondering whether there’s a homoerotic tinge to his feelings for Tristan. Sven Nilsson is a reflective, noble Mark.

The whole, whatever its flaws, still strikes me as an overwhelming experience. This may be something of a collector’s item – but it should also be an essential item in the collection of anyone who cares remotely about Wagner, and about Tristan in particular.

Tim Ashley

| Cetra LO 73 | |

| Nuovo Era, Archipel, Myto, OOA, OA |

A production by Hans Zimmermann (Premiere)

There are cuts in this performance: in Act 1, Scene 5, from “Müh’t Euch die?” (Tristan) to “warum ich dich da nicht schlug” (Isolde), and from “Geleitest du mich” to “‘… zu sühnen alle Schuld.'” (Isolde); in Act 2, Scene 2, from “Dem Tage! Dem Tage!” (Tristan) to “dass nachtsichtig mein Auge wahres zu sehen tauge” (Tristan), from “Tag und Tod mit gleichen Streichen” (Isolde) to “ewig ihr nur zu leben?” (Tristan), and in Scene 3, from “Wozu die Dienste ohne Zahl” to “Da liess er’s denn so sein” (King Marke) and from “Nun, da durch solchen Besitz” to “meiner Ehren Ende erreiche?” (King Marke); and in Act 3, Scene 1, from “Isolde noch im Reich der Sonne!” to “die selbst Nachts von ihr mich scheuchte?” (Tristan), from “Muss ich dich so versteh’n” to “Zu welchem Los?” (Tristan), from “Die nie erstirbt” to “Der Trank! Der Trank! der furchtbare Trank!” (Tristan). [Jonathan Brown]