Die Walküre

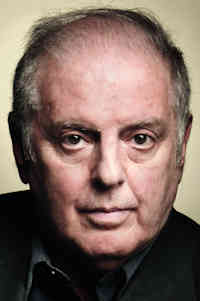

| Daniel Barenboim | |||||

| Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

| Siegmund | Simon O’Neill |

| Hunding | John Tomlinson |

| Wotan | Vitalij Kowaljow |

| Sieglinde | Waltraud Meier |

| Brünnhilde | Nina Stemme |

| Fricka | Ekaterina Gubanova |

| Helmwige | Susan Foster |

| Gerhilde | Marie Danielle Halbwachs |

| Ortlinde | Carola Christina Höhn |

| Waltraute | Ivonne Fuchs |

| Siegrunde | Leann Sandel-Pantaleo |

| Grimgerde | Nicole Angel Piccolomini |

| Schwertleite | Anaïk Morel |

| Roßweiße | Simone Schröder |

| Stage director | Guy Cassiers (2010) |

| Set designer | Enrico Bagnoli |

| TV director | Emanuele Garofalo |

After the unusual ballet/opera staging of Rheingold that began Guy Cassiers’ Ring cycle, this Walküre is a more conventional affair. The Eastman Ballet Company, who were an almost continual presence in Rheingold (review here) are here in little evidence, the only choreography a few figures projected onto the backdrop. Similar, though, is the colour scheme and visual profile, so again we have an uncluttered stage, with just a few props, all large and steeped in symbolism, and bathed in pastel blue and green shades. The costumes suggest decaying Victoriana, imagery that goes back to Chéreau but that has been revisited many times since, most recently in the Tankred Dorst Ring Cycle at Bayreuth.

By this second instalment, it is now clear that Cassiers takes more interest in the Personenregie than he does on spectacle, which is clearly the right approach, given the dramatic abilities of his cast. It perhaps makes things more difficult for video director Emanuele Garofalo, but by weighing the montage more in favour of close-ups than wide angles, the film gives us all the detail we need.

Daniel Barenboim continues his reign of world domination as a Wagner conductor here. It has taken him a few decades to refine his approach, but this, and almost every other Wagner recording he has made in recent years more than make up for the rigid and unidiomatic offerings from his early years with the Berlin State Opera in the early 1990s. The conducting here is consistently proficient, and in many sections truly inspired. The way he drives the orchestra into the concluding pages of the first and second acts is as exhilarating as you’ll hear anywhere. Barenboim is clearly aware of this, and a close-up on him the moment the first act finishes shows him exhausted but clearly brimming with pride at what he has just achieved. The La Scala orchestra plays well for him. In comparison to his Berlin forces, the string sound isn’t as rich and the low brass lacks weight. But the woodwind soloists are particularly fine, and the orchestra operates brilliantly as an ensemble for each set piece and scene change.

Every member of the cast is world-class, but that doesn’t make the casting even. The standout performances are from Waltraud Meier as Sieglinde, John Tomlinson as Hunding and Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde. Simon O’Neil is a proficient Siegmund, but he lacks experience and he could do with more metal in his voice. He must be at least 20 years younger than Meier, so it takes a leap of imagination to believe them twins. Throughout their exchanges, there is a feeling that she is showing him what to do, leading the drama simply through the greater force of her experience. As with many recent performances in which Tomlinson has taken a subsidiary role (his Pogner at Covent Garden last year also comes to mind), the only problem with his performance as Hunding is the extent to which he overshadows and actual bass lead, Vatilij Kowaljow as Wotan. Tomlinson’s Hunding has it all: power, menace and an electric stage presence that allows him to dominate the first two acts despite his relatively brief appearances. Kowaljow in not deficient as Wotan, his voice has power and character, his pronunciation is excellent and his acting isn’t bad, it’s just that he’s not John Tomlinson, whose Wotan will live on in the memory, even without the man himself reminding us of it by actually being present on the stage.

Some aspects of the stage design seem a little under ambitious, especially given that this is a co-production between two of the world’s greatest opera houses. Even so, the small devices carry their symbolic weight just as well as the large ones. A spinning sphere appears above the stage midway through the first act, with letters, symbols and colours projected onto it, an ambiguous psychological device but not an undue distraction. Long ribbons hang down across the stage in the second act, efficiently representing the forest setting in the later scenes. The valkyries’ horses appear as a huge, static bronze-effect prop at the back of the stage. The whole issue of horses in the Ring cycle is touchy, with many directors seemingly of the opinion that physical representation risks fetishising them. In Cassiers’ production, physiologically engaged with the work on so many levels, that’s never a risk.

The video of the staging was made for Italian television, and, as with Rheingold, the programme opens with a title sequence accompanied by an annoying montage of Leitmotifs. But the filming itself is well done. The leads have radio mics, affording immediacy, although the Valkyries do not, and sound distant. Voices and orchestra are mixed into a fairly harshly separated stereo (I haven’t heard the surround), but this doesn’t disorientate too much.

A high recommendation, then, for this Walkürie, well worth seeing, especially for the contributions, both musical and dramatic, from Meier, Tomlinson, Stemme and, of course, Barenboim himself.

Gavin Dixon | 2 December 2013

I gave a rather mixed reception to the first Rheingold instalment of Barenboim’s new Ring cycle on video a couple of months back. I am pleased to be able to report that some of the most desirable features of that release are retained in Die Walküre while other of the less enticing elements have been jettisoned. In the first place, the sets by Enrico Bagnoli and the producer still retain the sense of Nature as an essential ingredient in the Wagnerian world view, even though the composer’s specific instructions are not always complied with.

The water which covered the stage in Rheingold has been reduced to a small pool at the centre of the stage in Act One of Walküre. From this Sieglinde draws the water with which she refreshes Siegmund and into which she looks as she sings of her vision of her own face in the brook. The latter stages of Act Two are set not in the rocky wilderness that Wagner specifies but in a thick tangled wood which serves well to conceal the comings and goings of the various characters. This also serves to provide a spectacular curtain as Wotan in his wrath seems to set a spectacular forest blaze. The elements of realism extend also to a gigantic hearth in Hunding’s house. This appears to have consumed the best part of a couple of tree trunks, a rather pallid moon for the closing of the same Act, and bevies of horses for the Ride of the Valkyries. The latter are less satisfactory, since it is all too clear that we are seeing a series of repeated projections on a film loop. The appearance of the same horses as statuary in the first part of Act Two has an unfortunate overtone of monumental masonry at Versailles or some other palace. This is not aided by the fact that Wotan seems to drag the whole montage offstage with him when he leaves at the end of his monologue. One is pleased to see that the often intrusive element of dancers which sometimes jarred in Rheingold has now gone. Instead there are just two acrobats on stage to provide spectacular effects during the Ride of the Valkyries. As before, Guy Cassiers’s production sticks pretty closely to Wagner’s stage directions. We don’t get such glosses as a posse of heavies to accompany Hunding. The Valkyries are kept offstage when the music requires this. Also the Volsung twins don’t seem about to consummate their incestuous relationship on the spot in Hunding’s house – with the husband sleeping next door? – but run off into the forest as the curtain falls.

There are a couple of minor alterations to Wagner’s scenario. The first and second parts of Act Two are clearly differentiated into two distinct settings. The music to accompany the entry of the fleeing Volsung twins is treated as an interlude between the two scenes. As the Valkyrie approaches Siegmund in a vision, the forest becomes suffused with a silvery light. This emphasises the other-worldly nature of the scene, with normality only restored as the dreaming Sieglinde wakes up. This, together with Barenboim’s measured approach to the Todesverkundigung, makes for a real dramatic experience. This is secured without the need for any of the anointing and body painting to which some producers resort in an attempt to provide action for this essentially static scene. The only problem is that the silvery light resolves itself into a series of numbers and letters which stream up and down like a wayward airport terminal departures board. I cannot discern any purpose to this, although it is only really visible in close-up. When the viewer becomes aware of it the result tends to distract from the central characters in the scene as one tries in vain to read what is going on.

The admittedly complicated comings and goings at the end of the Act are somewhat differently treated from Wagner’s perfunctory killing of Siegmund. Although it is not always easy to see what actually happens on stage here, it is clear that Wotan comes behind Siegmund to break his sword and then pushes him forward onto Hunding’s weapon. In this he is thus more immediately complicit in his son’s murder. Siegmund does not die immediately, but reaches out his hand to Sieglinde as she is hurried away by Brünnhilde. Hunding then comes forward and delivers the coup de grace on the loud timpani roll which follows the fleeting reference to the Ride of the Valkyries. Wotan in the meantime stands rooted to the spot until he kills Hunding and then sets fire to the forest in the spectacular manner which I have already described.

Cassiers is not the first producer to find Wagner’s original scenario unsatisfactory; Patrice Chéreau and others have introduced a group of armed men to accompany Hunding in hunting down the fleeing twins. Even the usually faithful Otto Schenk preserved Siegmund’s life long enough to allow him to recognise his father before he died in his arms – a very moving interpretation of the music, and one which fits well with the emotional outburst from the cellos at that point.

There are only two characters from Rheingold who reappear in Walküre. It was originally the intention that both René Pape and Ekaterina Gruberova as Wotan and his wife should reprise their roles in this production. However Pape fell ill and withdrew at the last minute, and his place here is taken by the young Swiss-Ukrainian bass Vitalij Kowalijow. It has to be said that he does not yet fully inhabit the role, but his interpretation seems to be closely modelled on that of Bryn Terfel with the same manic look in the eyes; we see both of these quite clearly throughout. He has yet to achieve the same degree of ability to sing quietly while retaining intensity in his delivery. During his long Act Two monologue a large globe is suspended turning above the stage. This comes to a rather delayed halt at the words “Das Ende!” His singing in the forceful passages is always firm and noble, but one does sometimes wish for the ‘muffled’ tone that Wagner repeatedly specifies in the earlier stages of his monologue. Gruberova is a tower of implacable strength in her one scene.

It is extraordinary to see that this whole production has been taken from a single performance. The general standard of accuracy is very high but there are inevitably some points of concern which would surely have been rectified if more footage had been available. These particularly affect the performance of Simon O’Neill as Siegmund. He was clearly suffering from laryngeal problems which not only leads to a passage of hoarseness during his Spring Song but also a few frogs in the throat during Act Two. These do however serve to reinforce the impression of a man at the end of his tether. He has a nicely ringing tone otherwise, but his voice lacks sheer romantic ardour and he seems to have difficulty riding the orchestra during the more strenuous passages at the end of Act One. As his sister, Waltraud Meier is a tower of strength and dramatic ability just as one would expect. Only during her final delivery of “O hehrstes Wunder!” does one feel a lack of sheer heft in the upper register. She makes a virtue of necessity here by delivering the passage as an expression of interior emotion. The sheer impact of a singer like Jessye Norman is missing. On the other hand, she and O’Neill make a more believable pair of Volsung twins than Norman and Gary Lakes did in the Metropolitan production. She is properly cowed by John Tomlinson’s louring Hunding – that is once an unfortunate momentary pitch uncertainty during his opening line is out of the way. It was hard to imagine Norman’s assumption of the role being frightened of anything at all.

Nina Stemme is properly fearless throughout as Brünnhilde. Her voice has darkened since her Isoldes during the 2000s but her notes remain true. She delivers a thrilling Hojotoho! on her first entrance. She is not a steely goddess in the Birgit Nilsson mould, but rather a more womanly Valkyrie in the style of Rita Hunter or Martha Mödl. She is without the unsteadiness and sometimes curdled tone that sometimes afflicted the latter. This pays real dividends in the Todesverkundigung and her extended scene with Wotan during Act Three. Indeed she is quite simply the best Brünnhilde since Nilsson, albeit of a very different stamp. There is not one moment in her delivery of the score that finds her wanting.

The Valkyrie girls are a good collection – plenty of dramatic interaction with the principals, too – with no weak links. However; the production of the second part of Act Three is the weakest link in this video. In particular the closing Magic Fire is a particularly feeble moment, with a number of lanterns descending from the flies like a collection of nightclub illuminations. These only gradually seem to catch alight towards the very end just before the curtain closes. Incidentally the La Scala audience is exceptionally well behaved here, refraining from applause until the music has actually finished. God knows one does not want overkill at this point – I remember the old Sadlers Wells production – in the days before English National Opera – where the Coliseum smoke machine went wild and flooded the whole of the stage, the orchestra pit and the auditorium with fumes of dry ice – but this is just weak. Possibly something went wrong with the production here, with a lighting cue missed or muffed, which could not be corrected in this single performance; but reviews of the live presentation seem to imply that this was what the producer intended.

Nonetheless, despite these reservations, this is a very good performance of Die Walküre indeed, with a generally superlative cast. Daniel Barenboim is a conductor at once powerful and sensitive. To take just one example of many; at the point when the Valkyries are discussing where Sieglinde is to be hidden, at the mention of Fafner Barenboim reins in the tempo as the Ring motif enters, with a sinister frisson which casts a pall across the music. I don’t remember ever having heard this done before and it works superbly. The avoidance by the producer of extra-musical glosses is welcome. As a general performance with superlative singing of a more or less faithful production this is superior to the Metropolitan Opera Walküre, the weak link in Levine’s cycle. All the singers are good actors with plenty of stage presence. There are no extras.

Paul Corfield Godfrey | Jan 2014

The opening night of the new season at Teatro alla Scala Milan is a gala event, the most glamorous in the entire Italian opera year.

Because it’s so high profile it attracts inordinate extra-musical interest. This year the big news was a huge demonstration outside the theatre protesting a 37% cut in arts funding. Violence broke out, many were injured. When the President of Italy, Giorgio Napolitano, and his entourage took their seats in the royal box, festooned with ten thousand roses, Daniel Barenboim made an impromptu speech supporting the protesters. “In the names of the colleagues who play, sing, dance and work, not only here but in all theatres, I am here to tell you we are deeply worried for the future of culture in the country and in Europe.” Massive applause. The President joined in.

Barenboim’s never been afraid of standing up for what he believes in. He’s also a passionate believer in Wagner’s music and is one of its most committed interpreters. This performance of Wagner’s Die Walküre, broadcast live internationally, may not have been the most exemplary in orchestral terms, but there’s no denying Barenboim’s flair.

The cast was truly grand luxeas befitted the occasion. Rene Pape had cancelled a few weeks before but there were stars aplenty. Waltraud Meier, Nina Stemme, Ekaterina Gubanova, John Tomlinson, Simon O’Neill and Vitalij Kowaljow, replacing the indisposed Rene Pape.

Waltraud Meier is one of the greatest Wagnerians of all time. Any opportunity to hear her cannot be missed, for she has created all the roles and understands their place in the grand scheme. Although she’s no longer in the first bloom of youth, her artistry is such that she can create a Sieglinde so ravishing that she seems transfigured. Sieglinde’s past has been too traumatic for her to be an ingenue. so Meier’s interpretation emphasizes the way Seiglinde blossoms as love awakens her, like a parched plant unfurling after a long drought. When Meier sings “Du bist der Lenz”, her voice warms and opens outwards. It’s so expressive that she creates the idea of the world ash tree bursting into leaf despite the barren surroundings.

Wonderful as Meier is, even she is outclassed by Nina Stemme’s Brünnhilde. Stemme is so lively and vivacious that she completely dispels any memories of historic, matronly Brünnhildes, with metal breastplates, horned helmets and spears. Instead, she’s dressed in what could pass as a modern if quirky evening dress, a blend of lace and bombazine with hints of Goth and punk. The costume (Tim van Steenbergen) fixes Brünnhilde at once in Wagner’s world of political rebellion and in present day ideas of generation conflict.

Stemme’s youthful energy and spark highlight her idealism and high principles. She’s not intimidated by Wotan, however much she loves him. Here, already in germination, is the Brünnhilde of Götterdämmerung who will defy death itself to right the wrongs that have gone before. Stemme’s voice pulsates with intensity, and softens with tenderness, her control firm and measured. Stemme’s vigour might have been even more impressive against a more dominant Wotan, but Vitalij Kowaljow was adequate rather than brooding. Nonetheless, of the male singers in this performance, he held up best.

John Tomlinson’s Hunding was more genial than malevolent, more aging rock star (complete with pony tail) than abusive brigand. Sieglinde might have been more bored than cowed. Still, everyone loves Tomlinson and the role isn’t huge. More worrying was Simon O’Neill’s Siegmund. Apparently he’d been indisposed in rehearsal. Perhaps he should have cancelled, for he had vocal problems from the start, After his voice cracked on “Schwester!”, things deteriorated. Since O’Neill isn’t especially mobile physically, he couldn’t fall back on acting skills when the voice failed. There is no shame in cancellation, and it’s better not to risk long term damage.

Ekaterina Gubanova’s Fricka was superb, elevating the role from a minor part to something far more profound. Usually the role is unsympathetic as our feelings about Hunding are negative, and it’s Fricka who demands that he be revenged, even though he married Sieglinde by force. Gubanova looks and sings with youthful radiance, connected more to the idea of growth and refreshment than to barrenness and drought. After all she stands for moral principles, just as Brünnhilde does. Wotan defiles marriage by scattering offspring everywhere, destroying many lives. Fricka stands for good, even if she’s stern, as Gubanova’s interesting portrayal suggests.

Unfortunately the direction and staging did little to develop the ideas inherent in the opera and in the superb performances by Meier, Stemme and Gubanova. Hunding’s house in the First Act was very well expressed – a cube of mirrors, glowing with light, encroached upon by dark chaos. Perhaps this was what Guy Cassiers, the director, referred to as the inward-looking paranoia of gated communities, when interviewed. After all, Hunding’s hearth is a down-market Valhalla and Hunding was a bandit, just as Wotan and Alberich got ahead through deception.

Yet this good idea didn’t develop. Act Three was a forest of vertical slivers lit by green light to suggest a forest, nothing more. The magic fire in Act Three was just silly. Nonetheless, compared to the recent Met Das Rheingold (Robert Lepage) Cassier’s direction had merit, especially in terms of Personenregie and vocal finesse. With experienced stars like Meier, Stemme and Gubanova, he could hardly go wrong. One could imagine a truly original ground-breaking interpretation of Die Walküre with stars like this but it’s too much to expect in reality. This La Scala Die Walküre wasn’t remarkable in itself (apart from the three leading female roles) but could spark off further insight that might bear fruit in future productions.

Anne Ozorio | 11 Dec 2010

This was opera magic where Daniel Barenboim brought out the full depth and passion of Wagner’s music. Rating: * * * *

In the centre of Milan stands La Scala opera house, with its four tiers of boxes ascending to two further tiers of row-seats, where many of the most serious opera lovers sit — and they can be unforgiving if things are not right. The opening production this year was Wagner’s Die Walküre, under the direction of principal guest conductor Daniel Barenboim, who took over five years ago. His opening night debut in 2007 was also Wagner, unusual perhaps for an opera house so closely connected to Verdi and Italian opera, but he has succeeded brilliantly, and during the final curtain calls he and the performers looked up towards the gods, acknowledging their applause.

What a performance it was, in a new production by Guy Cassiers, with simple abstract sets and clever video projections. While Verdi’s operas often feature powerful family relationships, that between Wotan and his daughter Brünnhilde in Die Walküre is the equal of anything in Verdi, and here we had a young and glorious Brünnhilde in Nina Stemme. In the final scene, embraced by her father, with warm reddish light falling on her bare shoulders, she was the perfect sleeping beauty to be surrounded by fire until woken by a mighty hero in the next opera of the Ring cycle.

That hero has yet to be born, but at the end of Act 2, Brünnhilde drags his mother Sieglinde — magnificently sung by Waltraud Meier — away from the fatally wounded body of her lover and brother Siegmund, strongly sung here by Simon O’Neill. After they leave, Sieglinde’s abandoned husband Hunding thrusts his sword deep into Siegmund’s dying body. This is too much for Vitalij Kowaljow’s sympathetic Wotan, father to Siegmund and Sieglinde, and as he sweeps a hand sideways, Hunding falls dead. But what a Hunding this was, sung by Britain’s very own John Tomlinson with rich, dark tone.

Sieglinde, yearning only for death at the start of Act 3, suddenly comes to life after Brünnhilde foretells her pregnancy, and her “Rette mich Kühne! Rette mein Kind!” (Rescue me, brave one! Rescue my child!) filled the auditorium.

This was more than a miracle, it was opera magic, and at the end of the final act, as red lighting bespoke the fire that would encircle Brünnhilde, an asymmetrical collection of 28 red lights descended from above. All praise to the production team and singers, but to no one more so than Barenboim, whose nuanced conducting brought out the full depth and passion of Wagner’s music.

Mark Ronan | 21 Dec 2010

Onstage in Milan, Shadowy Giants Visible in New York

Say this for Robert Lepage’s unfolding production of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle at the Metropolitan Opera: the concept is likely to have a certain unity and consistency. There is, after all, only so much you can do to distract from the workings of the giant mechanism that dominates the stage.

To a viewer trying to get a sense of Guy Cassiers’s production emerging at the Teatro Alla Scala in Milan from afar, via HD broadcasts, the issue seems less certain. The second installment, “Die Walküre,” which opened the Scala season on Tuesday, was carried live at Symphony Space (complete with the conductor Daniel Barenboim’s little speech protesting cuts in the arts, delivered in the presence of Italy’s president, Giorgio Napolitano). This came two weeks after a film reprise of the first installment, “Das Rheingold,” and the stagings seemed to emanate from different spheres (to seize the word suggested through much of the second act of “Walküre” by a large spinning globe of latitudinal strips, which in certain lighting resembled a disco ball).

The differences in casting — Vitalij Kowaljow replacing René Pape as Wotan in the same grimy-gold suit, Ekaterina Gubanova replacing Doris Soffel as Fricka in a different strapless gown — were mildly unsettling, though not insurmountable hurdles. But broad strokes of staging, based largely in lighting and projections, were put to vastly different uses.

One of the boldest and most memorable effects in “Rheingold” — where dancers often shadowed the characters, sometimes literally — came in the depiction of the giants, Fafner and Fasolt: huge backlighted silhouettes looming behind the singers of those roles. Here again were shadowy silhouettes, on the walls of Hunding’s dwelling (more a country estate, with a huge fireplace, than a rude hut, with an open blaze), but this time to no clear purpose: whoever stepped in front of the right light — whether Hunding, Siegmund or Sieglinde — became the giant of the moment.

Doing mostly without dancers here, Mr. Cassiers relied heavily on awkward mugging to spell the relative inactivity of the first act. Orgasmic mugging is not something you want to see up close.

The verdant spring revealed when the doors of the hut swing open was nowhere to be seen. Some forest greenery was simulated in the second act, but it gave way to an abstract rain of letters and numbers, streaming down ribbony columns.

The costumes again seemed to be telling many tales, few of them scrutable. The Valkyries trailed bustle-train appendages that at times evoked the rear ends of horses, though it seems unlikely that the designers would want to risk such an open invitation to mockery.

It is hard to say more on the basis of a video broadcast that imposes its own perspectives and emphases on the stage picture. There were undoubtedly effects that worked better in the theater, and perhaps even some that provided clear ties to the “Rheingold” staging.

Nor can much be categorically said about the singing, given the inevitable inadequacies of electronic reproduction, which can change the quality of a voice to some extent and boost the size a lot. In the case of Waltraud Meier’s Sieglinde, troubles with the microphone added to the uncertainty. But it was pretty clear that, despite a mostly strong and heartfelt performance, Ms. Meier was flat in a couple of spots.

Simon O’Neill was also strong in his first-act heroics but seemed to wear down in the second act. Mr. Kowaljow was a plausible Wotan: less stentorian than Mr. Pape, perhaps, but more menacing of mien.

Yet the real stars, as they came through here, were Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde, and Ms. Gubanova as Fricka: both powerful, clear and communicative. You wanted to hear those two, especially, in a house.

The orchestra responded strongly to Mr. Barenboim’s command, though the woodwind playing became erratic in the late going.

The video production was bare-bones, simply showing the interior of the house when nothing was happening onstage, without commentary. The titles, in slightly haphazard English, were jumpy and rife with confusing repetitions.

Chats of varying lengths were dropped into the intermissions — Ms. Meier and Mr. Cassiers after the first act, both speaking in English with Italian titles; Mr. Barenboim after the second, speaking in Italian with English titles — and each was presented twice. That Mr. Barenboim’s talk was derived from an interview before an audience became apparent with the applause that greeted his line “If Wagner were a butcher, he’d have made the best hamburger ever.” Otherwise translated, Wagner always got the mix of ingredients and the relative proportions just right.

JAMES R. OESTREICH | DEC. 8, 2010

Schwache Mailänder “Walküre”

Mit dem “Ring” glaubte das Opernhaus nichts falsch machen zu können – doch das vokale und optische Niveau des Eröffnungsabends enttäuschte. Vor allem die männlichen Darsteller konnten nicht überzeugen.

Mit Wagners „Ring des Nibelungen“ lässt sich immer punkten. So dachte man wohl in Mailand. Deshalb hat man sich mit dem Antwerpener Toneelhuis und der Staatsoper Unter den Linden zusammengetan, um eine Neudeutung dieser Tetralogie zu wagen: mit dem Berliner Opernhaus nicht zuletzt deshalb, weil dort wie an der Scala Daniel Barenboim das musikalische Sagen hat, auch wenn er offiziell nicht als Musikdirektor des italienischen Opernhauses fungiert. Der Bayreuth-erfahrene Barenboim zählt jedenfalls zu den bedeutendsten Wagner-Interpreten der Gegenwart. Was kann bei einer solchen Konstellation noch schieflaufen? Zumal Barenboim auch an diesem Saisoneröffnungsabend, bei dem heftig vor dem Opernhaus demonstriert wurde – gegen die Finanzpolitik Berlusconis, die zahlreiche Kulturinstitutionen an den Rand ihrer Existenz geführt hat –, keinen Zweifel daran ließ, dass er seinen Wagner im kleinen Finger hat, was das eine oder andere zu ausführlich genommene Tempo nicht ausschloss. So spannend, aber auch bewegend wissen nur wenige diese Partitur nachzuerzählen. Zudem mit so viel Verständnis für die Möglichkeiten des Orchesters und die Gestaltungsfähigkeit der Sänger.

Hier galt es diesmal besonders zu differenzieren: Auch wenn sie am Schluss einhelligen Jubel entgegennehmen durften, ließ nämlich neben der nur durchschnittlichen Orchesterleistung auch das vokale Niveau zu wünschen übrig. Unkonzentriert, von Textausfällen geplagt, alles andere als gesanglich souverän gab Simon O’Neill den Siegmund. Auch John Tomlisons Hunding machte schmerzlich deutlich, dass der Sänger seinen Zenit längst überschritten hat. Dass mit Vitalij Kowaljow, der einen besonders blassen Wotan gab, sprachlich sorgfältig gearbeitet worden ist, will man ebenfalls nicht glauben. Es müsste mit seltsamen Dingen zugegangen sein, wenn alle drei just bei dieser Serata inaugurale – seit jeher die Visitenkarte der Scala – indisponiert gewesen wären. Angesagt wurde es jedenfalls nicht.

Gubanova, Stemme überzeugen

Mehr Fortüne hatte man bei den Damen, wenngleich Ekaterina Gubanova als Fricka über weite Strecken nur den Beweis erbrachte, eine besondere Begabung zu sein. Waltraud Meiers Sieglinde zu rühmen hieße Eulen nach Athen zu tragen. Wie sie diese Partie anlegt, mit welcher Finesse und Raffinesse in Ausdruck und Gestik, ist längst ein Klassiker. Übertroffen wurde sie nur von Nina Stemme als in jeder Hinsicht packende, innerlich aufwühlende Brünnhilde.

Auf diesem Niveau hätte man sich die übrigen Protagonisten gewünscht, denn auch die Walküren ließen punkto Artikulation und Phrasierung zu viele Wünsche offen. Wie auch die Inszenierung von Guy Cassiers: Was diesen „Ring“ auszeichnet? Dass spitz in die Höhe ragende Speere sich im zweiten Aufzug zu einer Waldlandschaft verdichten? Dass die anfangs über dem Bungalow schwebende Kugellampe sich schließlich vergrößert? Oder dass man sich im Laufe des Abends überlegen darf, ob eine altmodische Reiterskulptur besser zur Botschaft des Stückes passt als ihre mit modernen technischen Mitteln projizierte visuelle Auflösung? Lässt sich die Tatsache, dass Brünnhilde von der Götter- in die Menschenwelt verstoßen wird, nicht anders zeichnen als durch eine überdimensionale Schleife an ihrem Rücken, die zu einer Schleppe wird, in die eingewickelt sie die Finaltakte dieses ersten Tages des Bühnenfestspiels ausharren muss?

Weder mit namhaften Protagonisten noch mit originell scheinenden optischen Details lässt sich dieser Wagner bewältigen: Vorrangig ist und bleibt eine in sich schlüssige, die Handlungsfäden verdeutlichende wie den Mythos des Stücks erhellende Personenführung. Darauf hat man, scheint’s, vergessen. „Was gleißt dort hell?“, fragt Siegmund ziemlich zu Beginn. Ob Cassiers bei „Siegfried“ und „Götterdämmerung“, die jeweils zuerst in Berlin gezeigt werden, entsprechende Antworten finden wird? Ob man dafür eine stimmigere Besetzung engagiert?

WALTER DOBNER | 09.12.2010

Deuxième volet du Ring scaligère confié au nouveau maître des lieux Daniel Barenboim, cette Walkyrie séduit par ce qu’elle donne à entendre plus que par ce qu’elle donne à voir. Elle permet surtout de mesurer l’incroyable degré de maturité acquis, au fil des ans, par Daniel Barenboim dans sa maîtrise du répertoire wagnérien, depuis son premier Ring bayreuthien en 1988. On est d’emblée saisi par cette direction envoûtante, d’une densité jamais démentie, hypnotique, qui parvient à tirer de l’orchestre des trésors de poésie instrumentale. Attention, rien à voir avec la direction solide, charpentée et terriblement prévisible d’un Thielemann. Si on admire Barenboim dans Wagner, c’est pour sa capacité à surprendre, à prendre des risques, et à en faire prendre à ses chanteurs et instrumentistes, comme dans cette incroyable accélération à la fin du I, à couper le souffle (à partir de « Siegmund den Wälsung siehst du Weib ! »). Derrière ces effets dramatiques qui se révèlent indéniablement payants, il y a surtout une science accomplie de la dilatation et de la contraction du discours musical et dramatique, qui se traduit par un art des transitions qui n’est qu’aux plus grands (comme en témoigne, entre autres, le passage de la scène 2 à la scène 3 du II).

Face à une telle direction, il faut des chanteurs capables de ne pas perdre pied. C’est en grande partie le cas, d’abord et avant tout avec la Brünnhilde superlative de Nina Stemme, vocalement inapprochable, que l’on retrouve avec bonheur. Elle chante le rôle de la vierge guerrière avec une facilité (au moins apparente) qui ne manque pas de déconcerter. Les appels au II sont envoyés crânement, sans être propulsés comme des javelots à la parade, et l’on cherche en vain la moindre trace de fatigue dans la scène avec Wotan à la fin du III. Le couple de jumeaux est pour sa part quelque peu déséquilibré. Waltraud Meier n’a définitivement plus l’âge du rôle ? Qu’importe ! Elle brûle les planches et crève l’écran par sa présence scénique, en immense actrice qu’elle est, servie par sa beauté sculpturale. Que l’on se rassure, elle arrive toujours aussi bien à tricher avec sa voix. Une incarnation quasi miraculeuse. Face à elle, Simon O’Neill n’est sans doute pas le Siegmund le plus charismatique que l’on sache, le timbre est nasal, l’allure quelque peu empesée, mais il fait face au rôle avec sincérité et engagement, et réserve quelques très beaux moments (Annonce de la mort). L’idée de distribuer le vétéran John Tomlinson en Hunding relève du génie. Habitué des distributions wagnériennes de Barenboim (il fut notamment pour lui un Wotan, Gurnemanz ou Sachs de premier ordre à Bayreuth et Berlin), Tomlinson est un acteur né (on se souvient d’une production de Lohengrin à Bayreuth où il avait réussi ce tour de force de faire du roi Henri le personnage central de l’ouvrage !). Certes, la voix est en lambeaux, mais on a là une présence théâtrale unique, magnétique. Chaque mot est projeté comme du venin, et voilà enfin un Hunding qui comprend ce qu’il chante lorsqu’il lance à Sieglinde « Harre mein sur Ruh ! »… La Fricka d’Ekaterina Gubanova, au décolleté conquérant, assure vocalement, sa prestation étant servie par des moyens opulents et une excellente prononciation. On sera plus nuancé s’agissant du Wotan de Vitalij Kowaljow. La voix est saine et robuste, assurément, on apprécie les allègements dans le récit du II, mais c’est plutôt l’incarnation qui pêche : on cherche en vain l’aplomb, le vertige qui siéent au dieu des dieux. À la décharge du chanteur, il faut relever qu’il est singulièrement desservi par son accoutrement de chef de bande loubard, affublé d’une redoutable perruque, qui lui donne un air improbable de Daniel Guichard tout droit sorti de West Side Story.

Visuellement, la mise en scène de Guy Cassiers, si elle ne déchoit pas, ne marque guère. Sombre de climat, non dénuée de beaux effets visuels, recourant abondamment (en application des dogmes actuels) à des projections vidéo à la tonalité onirique, elle propose au spectateur néophyte, dans des décors gentiment stylisés, les symboles qui lui permettront de (re)trouver ses repères (les chevaux, l’épée, les arbres, la hutte de Hunding, le rougeoiement final…) Côté direction d’acteurs, on n’est pas chez Chéreau ou Kupfer. Les acteurs-chanteurs qui crèvent l’écran (Tomlinson, Meier, essentiellement) le font grâce à leurs qualités intrinsèques (on peut en témoigner). Les autres, plus d’une fois, paraissent livrés à eux-mêmes, et se réfugient dans des poses stéréotypées, à commencer par Wotan dont, par exemple, la colère du III (« Wo ist Brünnhild’, wo die Verbrecherin ? ») tombe à plat. Quelques trucs de mise en scène, plutôt bien trouvés, finissent par lasser, comme cette sphère tournoyante dont la vitesse de rotation est supposée refléter la progression du temps dramatique.

En définitive, c’est encore et toujours vers la fosse et les sortilèges du démiurge Barenboim que l’attention est attirée, car c’est bien d’elle que surgit l’étincelle qui, par moment, lorsque se trouvent sur scène les interprètes capables de la capter, hisse cette représentation vers des sommets d’intensité dramatique. Barenboim esquisse un sourire de contentement, dès la fin des derniers scintillements du Feuerzauber, avant de recevoir une véritable ovation du public, des chanteurs et de l’orchestre : rien que de très logique, et mérité.

Julien Marion | mar 20 Mai 2014

Lunghi applausi hanno salutato la recita conclusiva de “Die Walküre” di R. Wagner che ha aperto la Stagione d’Opera 2010-2011 del Teatro alla Scala di Milano. Le ragioni di un tale successo appaiono chiarissime in questo allestimento con la regia di Guy Cassiers. Il regista belga riesce nell’impresa di realizzare uno spettacolo contemporaneamente elegante ed espressivo, statico, ma non immobile, formale, ma non impettito. Uno spettacolo che sa evocare mirabilmente, se non proprio raccontare. Le istallazioni che adornano la scena sono strepitose: la capanna di Hunding, delineata da pareti su cui le moderne proiezioni si fondono alla perfezione con le più classiche ombre cinesi (curatissime le proporzioni che simboleggiano l’incombere minaccioso di Hunding su Sieglinde); la sfera, simbolo del potere, che, ruotando, dona tridimensionalità alle immagini durante la narrazione di Wotan. E ancora, il subitaneo scolorare degli elementi scenici in un bianco opalescente in corrispondenza del messaggio di morte o della profezia sul disfacimento del mondo divino; fino alla sensazionale scena finale, quando Brunhilde dormiente ed avvolta negli ampi drappeggi del suo abito, si eleva su di una pedana mobile, divenendo ella stessa un’istallazione vivente, avvolta dalle fiammeggianti lampade e le abbaglianti luci di Enrico Bagnoli. I costumi ad opera di Tim van Steenbergen sono anch’essi una commistione di passato e presente, con accessori dalla forte connotazione nordica (le gobbe e le estensioni posteriori delle gonne in pelliccia) e linee tipiche dell’alta moda che caratterizzano gli abiti dei personaggi femminili, realizzati per di più nelle nuances che vanno dal grigio fumo di londra al nero cangiante. Daniel Barenboim dirige con solido mestiere e discreta fantasia, un’orchestra che, qua e là, perde ispirazione, segnatamente nel finale del primo atto, dove Barenboim, pur incitando con calore, non ottiene l’effetto desiderato (e non manca di esprimere, spalle al pubblico, il proprio stizzito disappunto agli orchestrali durante lo scoppio dell’applauso). Se l’introduzione all’opera non freme come ci si aspetterebbe, gli slanci melodici di Siegmund e Sieglinde sono invece sensuali ed avvolgenti. Dopo un buon secondo atto, l’atmosfera prende finalmente quota: al terzo atto, l’orchestra si desta ed il suono, da spesso ed un poco greve, diviene ampio e carico di vibrazioni. Il cast, giunto alla fine della serie di recite, appare in forma. Waltraud Meier è un’artista di levatura, affascinante sulla scena e con un fraseggio dalle mille sfumature. La voce è parecchio stanca, purtroppo, e ad un registro centrale prosciugato di armonici, corrisponde un settore acuto ancora sonoro, ma meno fulgido d’un tempo. Nina Stemme (Brünhilde) ha dalla sua, un timbro abbastanza omogeneo e di bel colore; inoltre esibisce acuti che, seppur lievemente spinti da sotto, risultano ben saldati con il resto dell’estensione. Il suo personaggio, al pari della figura, è fiero e maestoso, con accenti patetici, laddove richiesto dalla parte. Ekaterina Gubanova nei panni di Fricka, oltre ad indossare il costume più bello di tutta la produzione, canta molto bene. La voce di mezzosoprano risuona compattissima ed è intrisa di colori voluttuosi; in più, sembra trovarsi davvero a proprio agio nei panni della moglie gelosa ed offesa, che viene a reclamare il rispetto dovuto dal consorte. Simon O’Neill è un Siegmund di routine, con voce forse non sufficiente a sostenere il ruolo nella sua interezza, ma la sua emissione è senz’altro convincente, con un’ottima proiezione di tutti i registri ed un riconoscibile impegno nella ricerca di legato nel “Winterstürme”. Il Wotan di Vitalij Kowaljow è penalizzato da un abbigliamento molto al di sotto del livello generale, con una giacchina argentata che richiama il peggior look dei primi anni novanta ed un trucco che lo fa assomigliare a Gene Simmons dei Kiss; però ha voce interessante che, pur senza la risonanza di molti interpreti del passato, lo conduce indenne all’incantesimo del fuoco nel finale. Interpretativamente, non pare avere molte frecce nel suo arco, mostrando pesanti limiti nell’espressione dei contrasti che affliggono il personaggio. John Tomlinson (Hunding) non è un cantante di primo pelo, però la voce è ancora ampia e densa; se poi si sorvola su certi oscillamenti del vibrato, il basso britannico compone un ritratto di tutto rispetto. Ottimo l’apporto delle otto valchirie, le quali, dopo un inizio a voce fredda ed un poco in sordina, recuperano terreno nella scena successiva, cavalcando la grande orchestra in modo ammirevole.

Andrea Dellabianca | Milano, 2 gennaio 2011

| Arthaus Musik | |

| Arthaus Musik |

Vitalij Kowaljow replaces René Pape as Wotan.

This recording is part of a complete Ring cycle.