Die Walküre

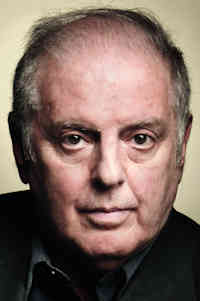

| Daniel Barenboim | |||||

| Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

| Siegmund | Simon O’Neill |

| Hunding | John Tomlinson |

| Wotan | Vitali Kowaljow |

| Sieglinde | Waltraud Meier |

| Brünnhilde | Nina Stemme |

| Fricka | Ekaterina Gubanova |

| Helmwige | Susan Foster |

| Gerhilde | Marie Danielle Halbwachs |

| Ortlinde | Carola Christina Hoehn |

| Waltraute | Ivonne Fuchs |

| Siegrune | Lean Sandel Pantaleo |

| Grimgerde | Nicole Angel Piccolomini |

| Schwertleite | Anaik Morel |

| Roßweiße | Simone Schröder |

Barenboim’s Scala Walküre–His Second Best

Daniel Barenboim’s Harry Kupfer-directed Bayreuth Ring Cycle on DVD from 1991-92 has long been a favorite. Kupfer’s direction, focusing so thoroughly on character(s) that it is impossible not to get involved in their plight, linked with a beautiful mise-en-scène that uses laser technology and conducting that strikes the perfect balance between, say, Böhm and Levine—i.e: between constant tension and long, myth-creating arcs—has made it the when-all-is-said-and-done set to return to on DVD.

Barenboim, in this new Walküre that opened La Scala’s 2010-2011 season, is competing with himself. As far as the conducting is concerned it matches the Bayreuth performance; if anything, the tense moments—from the very opening storm through the Wotan-Fricka argument and the finales of the first two acts—are even more edge-of-the-seat nerve-wracking, and the tender father/daughter and Act 2 brother/sister moments are even more lyrical and involving.

The La Scala Orchestra is not quite the equal of the Bayreuth forces, or at least their strengths are different: the dark brass Hunding motif in the earlier performance is terrifying but is lighter here, and the cushion of strings is more lush at Bayreuth. The orchestra in general has less bite than the Bayreuth forces, but there is some playing here that is absolutely beautiful both within and out of context, and it is to be treasured. The Todesverkundegung is as glorious and loving as possible, but the Ride entirely lacks the energy of the earlier set. Shall we call it a tie as far as Barenboim is concerned?

Like Kupfer, stage director and set designer Guy Cassiers (with Enrico Bagnoli) uses abstractions, but only up to a point, and his view can be confusing, abetted in its lack of clarity by Tim van Steenbergen’s costumes. The Valkyries are in ball gowns with huge bustles that sometimes look like the stingers of a wasp but mostly impede their movements. Suffice it to say that horses are either sculptures or projections, and they are joined by the bodies of heroes—also projected—during the Ride.

The first act features a white cube amidst darkness; what is supposed to be the entrance of Springtime is an opening of two of the sides of the cube without a hint of verdantness, and the sword is pulled out of a sliver of silver. A big, green spinning ball shows up and morphs and then disappears—does it go with the prom/disco dresses? The second act, oddly good-looking, still makes little sense: trees become long tubes with liquid bubbling in them, sort of like elongated lava lamps, and silver, floor-to-ceiling spear-like spikes later show up with just glimpses of greenery to be seen between them. Intermittently, numbers and letters are projected. After the big horse and big hero backdrop in Act 3, the stage becomes bare; Wotan puts Brünnhilde to sleep on the ground under a series of red heat lamps. After a while the ground rises to become a mound (rock?), where we last see the Warrior Maiden. Half of Wotan’s face is painted black and he’s untidy; he looks like someone trying to look like Bryn Terfel.

The twins are sung by Waltraud Meier and Simon O’Neill, and close-ups lead us to believe that their mother was in labor for close to 20 years, giving birth to the girl first. Meier, in occasional worn voice, is nonetheless magnificent as Sieglinde; a superb actress who listens as well as sings, her involvement never flags, and despite the tell-tale obvious aging process, she is vivid and moving. O’Neill, youthful looking but somewhat awkward, rises to every vocal occasion and has learned the value of stillness: he and Brünnhilde’s Announcement of Death scene is all the more powerful for its restraint. John Tomlinson, the Wotan of Barenboim’s Bayreuth reading, makes up in menace and acting what he lacks in vocal power as Hunding.

Vitalij Kowaljow’s Wotan is undercharacterized/under-directed. His baritone voice is lighter than we are accustomed to in this role, and he occasionally is driven to attempted bellowing for effect: keeping up with Ekaterina Gubanova’s big-voiced, offended, won’t-take-no-for-an-answer Fricka seemed a chore. He has presence and stamina, however. His soft interactions with Brünnhilde are, by contrast, deeply touching, aided of course by Nina Stemme’s remarkable portrayal of the Valkyrie. Her voice is rock solid and every note is well-placed and handsomely sung. The dark tones of the Todesverkundegung, soft delivery of her shame-felt last act confrontation with Wotan, and brilliance during her “Ho-jo-to-hos” keep the listener feeling endlessly secure—a true rarity with today’s Wagnerian sopranos. Close-ups do not do her any favors either: though still under 50, she appears matronly.

And so, this is a very well-sung and led Walküre that somehow does not manage to win many friends. The confused and unfocused direction, the sets that elicit little except a sporadic admiring glance, and, oh yes, at least one or two Valkyries who should be doing valet parking in Valhalla rather than singing and rescuing heroes, takes this out of the running for top prize. Stick with Barenboim ’91 or the strange Copenhagen Ring (though you’ll need it all to understand the director’s concept); traditionalists might prefer the Met production from the ‘80s under Levine. Subtitles are in all major European languages and Korean; the picture and sound are excellent and TV director Emanuele Garofolo wisely concentrates on the characters and their reactions, since there’s so little going on visually.

Artistic Quality: 8

Sound Quality: 8

Robert Levine

Wagner’s Ring of the Niebelungen is such a huge undertaking for any opera company that it is inevitably bound to involve some degree of compromise along the way. Even at a house as prestigious as La Scala in Milan. Their opening salvo of Das Rheingold wasn’t perfect by any means, but in the areas that counted – in the establishment of a distinct dark and moody setting, in Barenboim’s fine conducting and in the overall high quality of the singing – the Ring’s prologue was as promising an introduction as you could hope for a new Ring cycle at La Scala. The second chapter however, Die Walküre, brings a whole new set of challenges.

The degree to which Guy Cassiers’ direction for Das Rheingold successfully sets the tone for the rather more epic scale of the works to follow is however immediately clear from the outset. The darkness, the menace and the threatening tone carries over perfectly into the epic storms of creation and the flight of Wehwalt/Siegmund and draw us compelling into Die Walküre. The compromises that this section reveals however also gradually become apparent and it involves choices made in the casting and in the singing. Neither however are so great that they detract in any significant way from the overall success of this critical juncture in La Scala’s Ring cycle.

Most notably – although it’s by no means critical – there’s no consistency here in the casting of Wotan and Fricke. On the other hand, the casting is still exceptionally strong. René Pape and Doris Soffel, who weren’t entirely convincing in Das Rheingold, give way here to Vitalij Kowaljow and Ekaterina Gubanova, both of whom perform very well even if they don’t have the same degree of stature or personality as their predecessors. The other vital roles are strongly cast with Waltraud Meier as Sieglinde, Simon O’Neill as Siegmund, Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde and John Tomlinson as Hunding. On paper that looks impressive, and there are indeed some exceptional performances, but not all are quite perfect.

There is perhaps some degree of compromise in the casting of Waltraud Meier and John Tomlinson. Neither is at their peak now and it shows in places. The diminishing power of John Tomlinson’s voice that have been noted relatively recently (in his Gurnemanz for the 2013 BBC Proms Parsifal) aren’t quite as pronounced here, but it’s still not the powerhouse of earlier years. Tomlinson’s ability and presence however, his deep understanding of Wagner’s music and how it informs the characters even in a relatively minor role like Hunding, stand him in good stead here. The same could be said about Waltraud Meier, who is showing a little more restraint in her performances, but that works perfectly in keeping with Barenboim’s dynamic approach to the score here. In terms of experience, expression and sheer professionalism, not to mention a voice of quite lyrical beauty and true force where required, Meier however really comes through.

All the roles in Die Walküre are important to the overall fabric of the work, but the ones that can make all the difference are Siegmund and Brünnhilde. Simon O’Neill sets his own pace it seems, not always following the tempo set by Barenboim, but he sings well and gets across the necessary sympathy and nobility of his character. Nina Stemme however is just phenomenal as Brünnhilde, and that’s really what raises the overall high standard of this Die Walküre. Her’s is a voice of immense richness of timbre, but Brünnhilde is by no means a role that can carry the work in isolation. It needs to work alongside the other characters and that’s where the strength of the casting really shows. To use just one example, the critical scene of Siegmund, Sieglinde and Brünnhilde in the woods during Act II, Scene IV is telling in this respect. It’s just stunning, the singing and expression of sentiments coming together, working in perfect accordance with the staging (light shading trees turning into shards of ice) and with Barenboim’s orchestration to haunting effect.

It’s Daniel Barenboim of course who is instrumental in bringing all this together quite so successfully. He adjusts somewhat to the strengths and weaknesses of the singers in a way that gets the very best out of them, but he also responds to the full dynamic of Wagner’s score, allowing the lyricism, romanticism of the work to be expressed in the simple beauty, tone and melody of the music itself as much as in the measured force of the delivery. Act I in particular benefits from a more sensitive and lyrical approach to Siegmund and Sieglinde’s encounter, even as the menace still broods dramatically in the background, suggesting that there is still a possibility of averting the tragedy to come at this stage, or at least that these characters offer the hope of redemption. Barenboim is just as expressive when that menace erupts, in the shimmering ecstatic raptures and in the heft of emotions that underline them. It’s a sheer tour-de-force that allows the score space to breathe and assert it own power without ever overplaying its hand or over-emphasising.

That all works in perfect accord then with Guy Cassiers’ understated direction for the stage, which is more about mood than strict representation. In this respect it’s not dissimilar to the Met’s recent Ring cycle, only with a set here that achieves that necessary impact much better and in a far less complicated manner than the Met’s Machine. Following on from Das Rheingold, Hunding’s lodge is a cube of light in what looks like a dark cave of glistening light projections. Act II, with a spinning globe connecting Valhalla to Earth, remains abstract but attractive to watch and feel without there ever being any sense of a “concept” being forced on the work and without distracting from the performances. The circle of fire conclusion is less of a spectacle, but that’s in tune also with the simplicity and beauty of the line established by Barenboim’s conducting of the work. It’s not exactly traditional, but it all looks gorgeous and works well.

The Blu-ray from Arthaus looks and sounds fabulous, the full-HD image and the PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio sound mixes perfectly representing the essential tone of the production and the performances. Other than a couple of trailers, there are no extra features on the disc. The BD50 Blu-ray is region-free and subtitles are in German, English, French, Spanish, Italian and Korean.

Keris Nine | 14 November 2013

The legendary 1992 Barenboim and Kupfer Bayreuth Ring is a hard act to follow – right at the top of most rankings of filmed Ring cycles and probably one of the best recorded cycles period. But the 2010 Ring cycle at La Scala, conducted by Daniel Barenboim and produced by Guy Cassiers, was very well received and Arthaus are to be thanked for bringing the cycle out on DVD and Blu-ray with very fine sound and picture.

Cassiers’s staging of Die Walküre is imaginative and engaging, deepening the drama rather than detracting from it. Hunding’s hut is more psychodrama than habitation, which is absolutely fine in my book – the only feature is the sword left by Wotan in the tree trunk. Acts II and III are also uncluttered, with skillful use of video projections and an unusual but successful representation of the forest through thin hanging strips. The horses are represented statically through statues, while color changes within a predominantly blue and green color scheme are used to good effect.

John Tomlinson represents the main continuity with the 1992 cycle. Then he was an inspirational Wotan. Here he sings the much more modest character role of Hunding and sings it very well indeed. So well, in fact, that he rather overshadows Vitalij Kowaljow’s Wotan. The singing from the other two principals besides Hunding in Act 1 is very strong. Simon O’Neill is a fine Siegmund, at the lyrical end of the spectrum but rock solid. The everlasting Waltraud Meier (who sang Waltraute in the 1992 cycle) is a wonderful and passionate Sieglinde. The duet in Scene 3 is dynamically conducted and very successful. The partnership continues to work very well in Act II, where Meier is very moving as Sieglinde and O’Neill is absolutely at his best in the duet with Brünnhilde while Sieglinde sleeps.

To the extent that the cast has a weak link it is Kowaljow, but he gets much better as the evening progresses. At the beginning of Act II he lacks depth and presence and Ekaterina Gubanova’s Fricka seems to get the better of him. She is certainly more forceful, although herself lacking some expressive nuances. Kowaljow warms up in the second scene, particularly in the long soliloquy. He couldn’t really be described as a tragic hero, but by Wotan’s Farewell at the end of Act III he is sounding majestic.

Nina Stemme’s Brünnhilde comes into Act II firing on all cylinders and manages to raise Vitalij Kowaljow’s game. Stemme acts very well, capturing Brünnhilde’s loss of certainty and lack of comprehension during the initial encounter with Wotan and then her grappling with the consequences of being more faithful to Wotan’s wishes than he himself is able to be. Stemme has a fine voice and can modulate it expressively. She and Meier are very superior singers indeed.

Daniel Barenboim cements his reputation as an outstanding Wagnerian. The timings suggest slow tempi, but the music flows dynamically and dramatically. This Walküre is highly recommended. It does not scale the heights of the 1992 Bayreuth recording, but it is an intelligent production with an outstanding conductor and some of today’s finest Wagner singers.

José Luis Bermúdez | 2014

This was opera magic where Daniel Barenboim brought out the full depth and passion of Wagner’s music. Rating: * * * *

In the centre of Milan stands La Scala opera house, with its four tiers of boxes ascending to two further tiers of row-seats, where many of the most serious opera lovers sit — and they can be unforgiving if things are not right. The opening production this year was Wagner’s Die Walküre, under the direction of principal guest conductor Daniel Barenboim, who took over five years ago. His opening night debut in 2007 was also Wagner, unusual perhaps for an opera house so closely connected to Verdi and Italian opera, but he has succeeded brilliantly, and during the final curtain calls he and the performers looked up towards the gods, acknowledging their applause.What a performance it was, in a new production by Guy Cassiers, with simple abstract sets and clever video projections. While Verdi’s operas often feature powerful family relationships, that between Wotan and his daughter Brünnhilde in Die Walküre is the equal of anything in Verdi, and here we had a young and glorious Brünnhilde in Nina Stemme. In the final scene, embraced by her father, with warm reddish light falling on her bare shoulders, she was the perfect sleeping beauty to be surrounded by fire until woken by a mighty hero in the next opera of the Ring cycle.That hero has yet to be born, but at the end of Act 2, Brünnhilde drags his mother Sieglinde — magnificently sung by Waltraud Meier — away from the fatally wounded body of her lover and brother Siegmund, strongly sung here by Simon O’Neill. After they leave, Sieglinde’s abandoned husband Hunding thrusts his sword deep into Siegmund’s dying body. This is too much for Vitalij Kowaljow’s sympathetic Wotan, father to Siegmund and Sieglinde, and as he sweeps a hand sideways, Hunding falls dead. But what a Hunding this was, sung by Britain’s very own John Tomlinson with rich, dark tone.Sieglinde, yearning only for death at the start of Act 3, suddenly comes to life after Brünnhilde foretells her pregnancy, and her “Rette mich Kühne! Rette mein Kind!” (Rescue me, brave one! Rescue my child!) filled the auditorium.This was more than a miracle, it was opera magic, and at the end of the final act, as red lighting bespoke the fire that would encircle Brünnhilde, an asymmetrical collection of 28 red lights descended from above. All praise to the production team and singers, but to no one more so than Barenboim, whose nuanced conducting brought out the full depth and passion of Wagner’s music.

Mark Ronan | 21 Dec 2010