Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

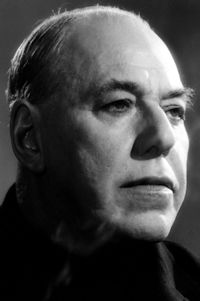

| Lovro von Matačić | |||||

| Coro e Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

| Hans Sachs | Giuseppe Taddei |

| Veit Pogner | Boris Christoff |

| Kunz Vogelgesang | Vito Tatone |

| Konrad Nachtigall | Giovanni Ciavola |

| Sixtus Beckmesser | Renato Capecchi |

| Fritz Kothner | Vito Susca |

| Balthasar Zorn | Ezio di Giorgi |

| Ulrich Eißlinger | Raimondo Botteghelli |

| Augustin Moser | Walter Brunelli |

| Hermann Ortel | Renzo Gonzales |

| Hans Schwartz | Silvio Maionica |

| Hans Foltz | James Loomis |

| Walther von Stolzing | Luigi Infantino |

| David | Carlo Franzini |

| Eva | Bruna Rizzoli |

| Magdalene | Fernanda Cadoni |

| Ein Nachtwächter | Silvio Maionica |

Considering its reputation as Wagner’s most accessible opera, “Meistersinger” can be vexing. An emotionally ambiguous work of nearly five hours — Act 3 alone is longer than all of Puccini’s “La Bohème” — its genial story of convention-bound medieval guildsmen learning to embrace tolerance and open-mindedness can’t mask the subtext of xenophobia (“Respect your German masters,” commands the final chorus) that made “Meistersinger” a favorite Nazi Party party piece, trotted out for everything from Hitler’s birthday to rallies in, yes, Nuremberg.

None of that heavy Teutonic history weighs on a sunny 1962 live performance from the Orchestra and Chorus of the RAI, Turin, conducted with sprightly energy by Lovro Von Matacic, and sung in Italian. The way Renato Capecchi indulges all manner of opera buffa growls, chuckles and squeaks as the comic villain Beckmesser, you’d swear he was Don Pasquale on a Bavarian holiday. And why not? The two characters are kindred spirits in their preening self-regard and superannuated leering. And Capecchi’s shameless Beckmesser is one of the most genuinely funny on disc.

Luigi Infantino and Bruna Rizzoli, as Walther and Eva, make a wonderfully fresh-voiced pair of young lovers, countered by Boris Christoff’s sternly imposing Pogner. Giuseppe Taddei brings warmth, magnetic virility and a mahogany baritone to the central role of Hans Sachs, the philosophically inclined cobbler-poet. (It’s a pity, with Taddei so fine in the part, that Sachs’s crucial Act 3 fit of anger is excised here.) With its decent enough stereo sound, this lovable, handsomely sung production is a must-hear for Wagnerians.

Joe Banno | August 24, 2008

Almost thirty years ago a century old tradition ended with the last performance of I Maestri Cantatori. From that moment on only Die Meistersinger went unto the boards as snobbery wanted operas to be performed in their original language, even when 90% of the public didn’t understand a single word. Wagner himself would have been flabbergasted at this decision, though I’m sure he would be the first to welcome ten years ago the redeeming factor: the surtitle. But together with the disappearance of Wagner in Italian or French there went astray another tradition as well: the stars (especially the male ones) of French and Italian opera no longer wanted to sing Wagner as they had to relearn their roles in a language often strange to them. Domingo is of course the big exception but what a wonderful Lohengrin Bergonzi (who studied the role in Italian) or Pavarotti could have sung. Therefore this recording is one of the last of a dying tradition and well worth hearing.

No, it is not a substitute for a German official recording as there are some traditional cuts (mostly in the Hans Sachs role) and the sound of orchestra and chorus is a little bit thin. I don’t think Myto was allowed access to the original radio tapes. But there are some interesting assets as well, the main being the noble Hans Sachs of Giuseppe Taddei. Usually booklets accompanying these pirate issues praise the performers to the sky but the anonymous writer of this issue dryly states that “Taddei impresses more by way of his volume than richness of phrasing”. This will come as a surprise to someone listening to the baritone in this role. Listen to his moving Flieder monologue, full of subtle utterances. And which postwar German baritone has the warmth of this well-focused voice that is so suited to the role ? There was always something of a bass-baritone in Taddei’s voice (he made his début as Heerrufer in Lohengrin) and therefore he easily encompasses the whole vocal range for the role. Second to him comes the surprising David of tenor Carlo Franzini, a real lirico with fine pianissimi in a role often sung by almost voiceless buffo’s.

Bruna Rizzoli, another neglected Italian lirico of the fifties and sixties, brings a sweet and beautiful soprano to the role fully convincing the listener of her youth and charms. With Luigi Infantino things go slightly downhill. One still hears the remains of what was once during and just after the war one of the most beautiful tenori di grazia in the world. His attacks on ‘Am stillen Herd’ and ‘Morgenlicht leuchtend’ are still magical: soft, sensitive singing of the highest order but at full voice the throatiness is now clearly discernible. Still, compared to most German tenors of the day and most gentleman of today he sings in a higher league.

Boris Christoff brings authority and gruffness to the role of Pogner. The Bulgarian clearly is not a very loving father because warmth and charm were never in his vocal arsenal but after all, how loving can a father be who offers his daughter to the as yet unknown winner of a singing contest ?

Renato Capecchi’s Beckmesser is more problematic. At his first utterance he reminds one immediately of his many Melitone recordings where he tries to make an impression by distorting his voice or gliding over the notes in his bad Corena-imitations. There is more to Beckmesser than just a bigoted preaching clown but Capecchi never delves deeper into the role.

Matacic is a phenomenon, even with an orchestra of the second rank. He actually takes his time, in fact he is slower than several German conductors. He doesn’t hurry along his singers but still succeeds in giving an impression of lively vitality. One never feels that the music comes to a standstill. The bonus is an interesting one: Boris Christoff singing in more or less acceptable German, Wotan’s ‘Leb Wohl’ from Walküre. Though the bass hits all the notes, the voice is definitely too low for the music and the colour is wrong. Christoff could express hate, resignation, pride, solitude but warmth or deeply felt love are not his. One feels all the time this is a Boris or a king Philip lost in another planet.

Jan Neckers