Der Ring des Nibelungen

| Michael Schønwandt | |||||

| Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Danish Opera Copenhagen | ||||||

Date/Location

Recording Type

|

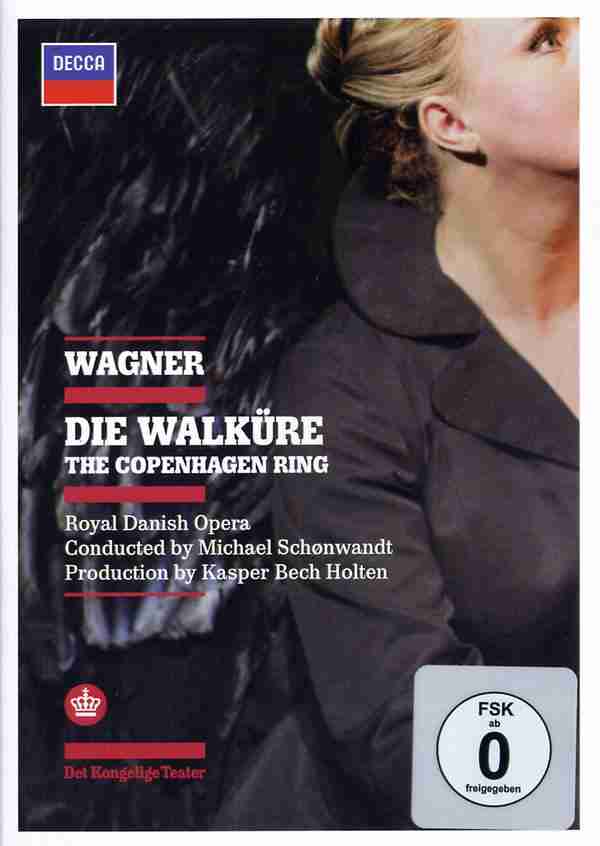

This 7 DVD set contains “The Copenhagen Ring” – the complete Nibelungen Ring, recorded from the three live Ring cycles performed by the Royal Danish Opera in 2006 in the new opera house located directly on the Copenhagen waterfront. The bonus material consists of a 30-minutes conversation between director Kasper Bech Holten and the Queen of Denmark (see below). The accompanying booklets include sections by Kasper Bech Holten on the production concept as well as background information on the cycle. Subtitles are available in English, French, German, Spanish, Chinese and Danish.

In brief, this was labeled The Feminine Ring, as the story is told in flash-backs from Brünnhilde´s point of view, spanning the 20th Century. While the Feminine viewpoint does not seem central in the final concept as it appears on DVD, the history-telling of the 20th Century does indeed: From the roaring 20´s of Rheingold to the hermetically closed and conservative 50´s via the liberation of the 60´s in Siegfried to the cruel Balkan-like partisan war of the 90´s in Götterdämmerung.

First of all, The Copenhagen Ring this is a very theatrical Ring. The tempi are high. Myriads of things take place simultaneously on stage. No one just hangs around passively in a corner. That the impression of this Ring indeed was stronger on DVD than live, may perhaps be attributed to the very close-up camera shots revealing the extraordinary detailed stage direction.

In brief, the musical side was an unequivocal success: Michael Schønwandt´s Royal Danish Orchestra sound was gloriously transferred to DVD, with even greater power and more lucidity than I remembered it from the live performances.

The singers were all excellent actors and looked their parts. Furthermore, the singing was never less than average and casting of many of the crucial characters were on the highest international level (Stephen Milling, Stig Andersen, Irene Théorin etc.).

However, the most controversial aspect of this Copenhagen Ring DVD release undoubtedly will be the actual filming, as The Copenhagen Ring approximates a film in its own right rather than a recording of a live operatic performance:

18 cameras were used, several providing views not accessible for the audience (from the prompters box, from above, from the side-stage, from under the tables, from the bottom of Mime´s sink etc). Everything was filmed very close up, closer than in any other operatic DVD I have encountered. And a tremendous amount of clips were applied – especially in Rheingold, I gather the camera angles were changed at least once every 5 seconds, providing a very flickering image. Furthermore several of the close-ups were shaky and initially off-focus, distinctly reminding of the works of Dogme-film directors such as Lars von Trier applying very close-up shots with hand-held cameras at odd angles.

Several of the singers turned out even better actors on the DVD than I remembered them in the theater, and on DVD nuances in the stage direction I never noticed before suddenly became apparent. Even the smallest wrinkle is seen, not always desirable though, and singers like Stig Andersen actually look older with the stage make-up. There is a distinct in-your-face effect to all this, which I suspect potential audiences will disagree wildly about.

Did I like the filmic aspect then? I am not sure, which, however mainly is of interest to myself. The question is, may the potential/actual buyers like it? Some undoubtedly will not. I´d especially predict younger audiences to find this high-tempo story-telling fascinating. For sure, it is never boring and will make a great introduction for those unfamiliar with the work.

I must admit to finding these quick camera shifts quite stressful making it almost impossible to focus on the music. By far the worst in Rheingold. But then I suppose it´s better being irritated than bored… Finally, one has to realize this is virtually a film on its own right and does not give an impression of how it was to be in the audience (as an audience member when this DVD was recorded, I should know).

The production of this Copenhagen Ring DVD is a major achievement from a relatively minor opera house. And impressive to have this released on DECCA instead of the odd backyard company I had expected…But local-patriotism aside, The Copenhagen Ring more than holds it´s own on the relatively small Nibelungen Ring DVD market. First and foremost I am positively surprised of the high musical quality of this Ring.

With an eye on the DVD competition, the only other demythologizing Ring production on DVD is the Stuttgart Ring, which The Copenhagen Ring DVD exceeds in both production and musical quality.

The only true traditional Ring on the DVD market is the Schenk/Levine Metropolitan Ring, which I cannot recommend despite some fine moments.

Of Kupfer´s two DVD Rings, the Barcelona production has the superior staging (but with very disappointing musical quality), while both staging and orchestra is superb in the other Kupfer Ring conducted by Daniel Barenboim in Bayreuth, not to be touched musically.

However the Danish Royal Orchestra perform on such high level that those not caring to look at Harry Kupfer´s naked Bayreuth Festival stage for 14 hours, may prefer The Copenhagen Ring.

Audi´s futuristic Amsterdam production is extremely beautiful, but so different from Kasper Bech Holten´s approach, that comparisons do not make sense (The Copenhagen Ring singers in general are slightly better than the Amsterdam team, though Haenchen´s orchestra is fine). And lastly, Patrice Chéreau´s Bayreuth Centenary Ring with the superb stage direction, slightly disengaging conducting, unfortunately has a disastrous casting of Siegfried. Again, very different.

As I do not necessarily mind looking at an empty, dark stage for 14 hours, as well as being a huge admirer of Daniel Barenboim, the Kupfer/Barenboim Ring still takes first place on my shelf. But after that, the field is entirely open..

I´d strongly recommend The Copenhagen Ring for the theatrical approach and musical quality. Indeed, the musical quality is so high that for those preferring modern productions with high tempi and easy-to-follow storytelling, I wouldn´t hesitate to recommend this as a first choice Nibelungen Ring on DVD. It may serve as a great introduction to the Nibelungen Ring for those not familiar with the work or with Wagner, as well. A comprehensive review of all commercially available Nibelungen Ring DVDs may be found here.

The Copenhagen Ring may well hold it´s own on the DVD market, also for those “only” intending to own one DVD version of the Nibelungen Ring.

The individual operas – Rheingold

A panoramic waterfront view of the new Copenhagen Opera House at dusk is shown before every performance. We then see Queen Margrethe of Denmark take her seat in the Royal Box just before the Rheingold begins (she attended cycle 2 as did I, but despite repeatedly freezing the screen, I didn´t manage to catch a glimpse of myself on row 14, when the cameras swept the floor section).

Irene Théorin now takes center stage. She is in the attick of her family´s mansion and she rummages through memorabilia in order to understand her past (in Götterdämmerung we learn that this takes place the exact moment Hagen and Gunther has left to kill Siegfried).

The Rheingold fits on one DVD. During the interludes, footage of Brünnhilde and her past is shown, probably attempting to highlight the Feminine story-telling aspect of the production.

The individual operas – Walküre

Many, including director Kasper Bech Holten, has named the moment Wotan tears off Brünnhilde´s wings the greatest of the Ring. I must confess to the minority view of never have thought anything particular of that scene…

Walküre, in my opinion, is the least successful of the four stagings, mainly due to the fact that the drama between Siegmund and Sieglinde vs. Wotan and Brünnhilde never seemed to function at quite the same level as the core political dramas in the other installments.

A 30-minute bonus feature included director Kasper Bech Holten in conversation with Queen Margrethe of Denmark (an avid Ring follower and very enthusiastic about this Ring) on the production, which the Queen has seen numerous times. Kasper Bech Holten appears very enthusiastic and engaging, hilariously interrupting the Queen, who doesn´t seem to take offense, numerous times….Kasper Bech Holten once again confirms that the sets for this Ring have indeed been thrown away, so there will definitely not be a revival.

The singers

Generel comments: There are no truly weak links among the singers, not even wearing international (as opposed to local-patriotic) glasses. All singers futhermore were excellent actors.

Wotan: Johan Reuter, despite a beautiful voice and convincing acting he seemed almost too naive as the young Wotan and somehow didn´t quite make the impression I´d expected him to.

James Johnson does not have a particularly large voice, which furthermore is almost approaching a true barytone. An excellent actor with a considerable talent for comedy and irony as well as vocal characterization. A very convincing portrait.

Brünnhilde: Irene Théorin´s Brünnhilde was even more convincing on DVD than live, the close-up shots revealing her as a vastly more convincing stage actress than I was aware of from sitting in the audience. And in her absolutely best voice, with a glowing middle register and a reasonable vibrato, she hits all the notes, most on pitch as well. Only in Götterdämmerung did she occasionally seem to tire vocally. Clearly among the best on DVD.

Siegfried: Superb performance from Stig Andersen. Truly a world-class Siegfried. He may be slightly strained on the top, which however does not detract from his performance as he is a formidable stage actor as well. Unfortunately the make-up makes him look even older than he (and Siegfried) is. Also fine as Siegmund (taking over the role from the originally scheduled Poul Elming).

Sieglinde: Solid performance from a Gitta-Maria Sjöberg with a distinguished golden glow in her middle voice. Not a large voice, and essentially lyrical, but capable of conveying the necessary drama.

Hunding: Stephen Milling´s truly evil and menacing Hunding was one of the highlights of the entire cycle and is beyond competition on on DVD (as well as on stage).

Hagen: Dramatically, Peter Klaveness is a splendidly terrifying and psychopathic Hagen. Unfortunately he is vocally underpowered and shaky. But this is clearly to be preferred to the opposite combination.

Alberich: Sten Byriel was dramatically convincing, but lacked some vocal power as well.

Fricka: Randi Stene was a stylish and elegant Fricka in all regards.

Erda: Vocally the part is slightly too low for Susanne Resmark´s maximal comfort. But she is a formidable as well as courageous stage actress and the scene from Siegfried showing her decay is unforgettable.

Mime: Bengt-Ola Morgny fits the image of Mime´s small and constricted mind exceedingly well.

Gutrune: Ylva Kihlberg has a very unique middle voice and is perfect as the white trash Gutrune.

Gunther: Guido Paevatalu is convincing as the white trash paramilitary Gunther, slightly more so dramatically than vocally.

Loge: Michael Kristensen was slick as Loge and vocally fine as well, though I missed some edge in the characterization.

Fasolt/Fafner: Stephen Milling demonstrated himself capable of an almost unbelievable dramatic change between his soft Fasolt and mesmerizing Hunding. Christian Christiansen, though not entirely on this level, was nevertheless a solid Fafner.

Waltraute – Fine performance from Anette Bod.

Others of note:

Both the Rhinemaidens, Valkyries and Norns were fine. Powerful performance from the choir in Götterdämmerung, revealing many of the choristers to be excellent stage actors as well.

The conductor and orchestra

Michael Schønwandt´s approach to Wagner does occasionally tend to be too passive for my taste. Just by observing him on the podium you immediately get an impression of a more light-hearted approach as opposed to watching the more heavy Wagnerians such as Daniel Barenboim.

With that in mind, I was positively surprised that Michael Schønwandt´s approach to the Nibelungen Ring stayed firmly away from Wagner light and instead he displayed some of the most forceful and pointedly conducting I have heard from him. And good to hear him apply the necessary force behind the brass section in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung.

Most importantly, Michael Schønwandt has an exceptional understanding of the structure of the work and manages to build up tension over long stretches of the score, instead of blowing out the fortissimos at every potential occasion. He creates a very detailed and balanced orchestral sound, where the wood-winds stood particularly out, sometimes even as audible as the brass section. More brass and density in the string section would still have been welcome, but these are artistical choices, obviously.

The tempi were firmly located in the middle (faster than Barenboim and Levine, slower than Haenchen and Boulez), occasionally verging on the fast side, particularly in the more grandiose sections (such as the prelude to Siegfried Act 3) where he keeps the tempo up. The sound was rather closely recorded (and in splendid sound quality as well), which helps create a dynamic sound image. Furthermore the coordination between the pit and the singers is virtually perfect and the sound is well balanced over-all.

Encouraged by all this, I then made the mistake to try some point-to-point comparisons with Daniel Barenboim in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung – and in that respect Michael Schønwandt´s reading does come out rather Wagner light, though…But so does everyone else´s. And though the Royal Danish Orchestra has become an international-level operatic orchestra, it really is quite unfair to compare them to the mighty Bayreuth Festival Orchestra. Apart from the fact, that this is one of the competing Nibelungen Ring DVDs on the market, and potential buyers may be interested in a take on the different approaches to the score:

In this respect, Michael Schønwandt is: More engaging than Pierre Boulez (Bayreuth); much more engaging and dynamic than James Levine (MET); simply better than Bertrand de Billy (Barcelona); slower than Hartmut Haenchen who is too fast in an otherwise well-played performance (Amsterdam); more brilliant than Lothar Zagrosek (Stuttgart). That leaves Daniel Barenboim (Bayreuth), who is untouchable. But then Harry Kupfer´s accompanying staging is substantially different from Kasper Bech Holten´s.

In brief – The highlights and lowlights

The highlights: Stephen Milling´s Hunding. Stig Andersen´s Siegfried. Iréne Théorin as Brünnhilde. Ylva Kihlberg as Gutrune. Susanne Resmark´s Erda in Siegfried. Michael Schønwandts orchestra. The detailed stage direction and sense of drama applied by Kasper Bech Holten and the production team.

Among the most powerful scenes: Wotan cutting off Alberich´s arm, Wotan visiting the frail Erda in Siegfried, the murder of civilians in Götterdämmerung

The lowlights: No element may be singled out as a lowlight. The controversial aspects, I´d predict to be:

The non-traditional staging (as always).

The non-traditional production of the DVD.

The bottom line (scale of 1-5, 3=average)

The ratings are given in comparison to the other Ring DVDs available, and the superb acting skills of several of the singers weigh in heavily here. After all it is a visual medium:

Johan Reuter: 3-4

Michael Kristensen: 3-4

James Johnson: 4

Stig Andersen as Siegfried: 5

Stig Andersen as Siegmund: 4

Irene Théorin: 4

Gitta-Maria Sjöberg: 3-4

Stephen Milling: 5

Sten Byriel: 3-4

Randi Stene: 4

Ylva Kihlberg: 5

Peter Klaveness: 4

Guido Paevatalu: 3-4

Susanne Resmark: 4

Anette Bod: 4

Kasper Bech Holten´s staging: 4

Michael Schønwandt and the orchestra: 4.5

Overall impression: 4

7 July 2008

When Bill Kenny, Regional Editor of MusicWeb’s Seen and Heard, visited the new opera house in Copenhagen in late December 2005 he waxed lyrical about the house itself. It’s a view I endorse as is clear from my review of Nielsen’s Maskarade, which I saw in January this year (2008). He was also deeply impressed and fascinated by Die Walküre in the new production by Kasper Bech Holten (His review is here). Now the full Ring appears on DVD. Having spent some intensive days in its company I feel a bit exhausted – especially since I listened through the reissue of Haitink’s Ring less than a week before – but I am just as fascinated as Bill.

Transporting the action to other, often more recent times, is no novelty, rather the contrary: it seems to be the norm today and quite often the result is more strange and alienating than illuminating. The Amsterdam Ring, directed by Pierre Audi, was a minimalist production with hardly any sets at all and the orchestra centre-stage. One of its great merits was the timelessness. The new Stockholm Ring, directed by Staffan Valdemar Holm (not yet on DVD) placed Das Rheingold in Wagner’s own time and then moved gradually into the 20th century and ended during WW1.

The same principle is employed here but Holten begins where Holm stopped, during the roaring ’20s and into the ’30s when the ideologies were structured. In Die Walküre we have reached the aftermath of WW2 and the cold war is raging, the structures have frozen; Siegfried represents young rebellion against the older generation in 1968. In Götterdämmerung belief in the future is being erased by the evil of the turn of the century – Holten mentions Bosnia or Rwanda. The malicious military commander Hagen and his soldiers stand as representatives for the raw oppression of the civilian population. The victims are Siegfried and Brünnhilde. Brünnhilde also runs through the story, pictured in sequences in Das Rheingold reading in old tomes. Thus the whole Ring can be seen as flashbacks from the present day. In Götterdämmerung during orchestral interludes she is again seen turning over pages in filmed sequences. 20th century history is set in relation to old Norse mythology, or vice versa: a really intriguing concept – but does it work?

There are anomalies of course. Wotan’s spear and Siegfried’s Nothung do not belong in the 20th century – you need to see them as symbols for their power rather than realistic attributes. The Valkyries are dressed in 1950s bloodstained evening gowns when they gather fallen soldiers. They also have very realistic wings and when Wotan denounces Brünnhilde in the last act of Die Walküre he brutally tears off her wings, causing her great pain. Holten refrains from doing what many present-day directors do: disregarding the text and what is actually sung. He trusts the onlookers’ intelligence to be able to filter out the anachronisms.

On the other hand there is so much inventiveness in characterisation of the roles. This helps create a believable or witty spirit of the time. Fafner in a wheel-chair is still able to kill Fasolt – a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Loge is a chain-smoking bureaucrat. Donner is there as the toughest of the gods, in leather-jacket and armed with a shotgun; his greatgrandson in our time would probably be a member of Hell’s Angels! Susanne Resmark in Das Rheingold is a spectacular Erda, Marlene Dietrich-like and seductive; no wonder Wotan got a nonet of Valkyries with her. He even kisses her in front of Fricka! When he visits her in Siegfried, dressed up in black suit with a bunch of roses and a bottle of champagne, she is old and sick, lying in bed and tended by a nurse.

Wotan himself, the leader who feels insufficient, his empire collapsing, has fallen into the same trap as many a business executive: he has taken to drinking and sips secretly from a hip-flask. His opposite pole, Alberich, is also a heavy drinker.

I could relate many more instances of finely observed everyday detail but I won’t deprive readers of the pleasure of finding out for themselves. Let me just mention another two: The appearance of the three Norns at the beginning of Götterdämmerung, not on stage but in the audience. It is an unforgettable moment when an onlooker in the first row, just behind the conductor, gets irritated by the lights, directed towards her, and suddenly stands up, seemingly to leave, pats Michael Schønwandt’s shoulder, points to the lights and starts singing: Welch Licht leuchtet dort? (What light shines up there?). The other is when we return to the cave on Brünnhilde’s rock. In this production it is on top of a roof, a lovely cosy, romantic, married-bliss balcony with flowers a-plenty and Siegfried carrying in the obligatory breakfast tray while Brünnhilde, in an advanced stage of pregnancy, is watering the geraniums.

This brings me back to the everyday detail that makes this Ring so easy to accept, to identify with. With all due deference to gods and heroes and giants, here they are humanized, brought down to a level where they are tangible and we feel that they are of flesh and blood. In spite of the evil that permeates so much of this drama, the impression that lingers most is the warmth and humanity. I have several times lately complained about the alienation that seems to be the order of the day in many opera productions; Kasper Bech Holten places human relations in the foreground. Rarely has there been so much closeness, so much bodily contact, so many warm looks – and hateful for that matter – and such close interplay between characters. Every word or gesture generates a realistic response; small reactions, hardly noticeable sometimes, but in the close-up filming of most scenes they are registered. Holten worked with this production from 2001 and obviously devoted himself to close reading of a kind that is rarely encountered. With a responsive cast of actors he has chiselled out completely believable characters and situations. Take the meeting between Brünnhilde and Waltraute in the last scene of act I. Brünnhilde is overjoyed when her old Valkyrie colleague appears but after some time, when Waltraute begins her soliloquy, relating the sad state in Valhalla, Brünnhilde is mildly interested and after some time she shows very clearly that ‘Oh, no! Why do I have to listen to this?’ Her eyes wander, her face becomes blank, her body is slightly turned away. Suddenly some words of Waltraute catch her, the body stiffens, the eyes look fixedly at Waltraute and her lips part slightly. This is again just one isolated instance of intelligent psychological direction and superb acting. There is plenty of it.

There are also some interesting and, possibly, controversial turns. The Rhinegold is a physical person, a young man swimming about in the Rhine – Alberich cuts out his heart. It is Sieglinde, not Siegmund, who pulls Nothung out of the ash-tree. Bill Kenny called it ‘girl-power’ and there is a good deal in that: she also takes the initiatives in the relation between them. Gutrune is a sexy seducer who wraps Siegfried around her little finger and Fricka is uncommonly strong-willed – actually more dignified than bitchy.

Hunding is not killed by Wotan; he is sent away to kneel before Fricka – a worse punishment than death for a brute like him. And, talking of humiliation, Wotan, in his ultimate degradation when meeting Siegfried, breaks the spear himself – no ‘girl power’ here but perhaps lack of ‘male power’. Finally a parallel to ponder upon: the siblings Gunther and Gutrune also seem to have a relation much more intimate than pure affection. There is room for various interpretations.

The production for DVD is extremely detailed and evocative – camera angles discriminatingly chosen to provide information in the subtext, often in short glimpses. Here the DVD viewer is at an advantage compared to the theatre audience. We don’t need to search for the focus of the action. I can’t find it said explicitly anywhere in the notes but I suspect that Holten has had a finger in the pie here too. The superb theatre machinery is innovatively employed and when the action takes place in two or even more storeys – sometimes simultaneously – the home-viewer is again a step ahead of the live onlookers. The plentiful use of close-ups also facilitates the understanding and experience of this complex drama. Here also lies the singular problem with this DVD production. When the cameras creep straight into the faces of the singers there can sometimes be an almost embarrassing closeness, comparable to the feeling when someone comes within my personal territory at a conversation. Moreover, and that’s the most troublesome point, a singer in close-up at fortissimo, velum fluttering, face distorted, isn’t a very flattering sight. Don’t let this deter you from acquiring this Ring, however; it’s worth some embarrassment.

So far I have focused only on the staging and some interpretative points of interest to give readers an idea of what kind of performance this is. But opera is also music and however fascinating a production is from a theatrical or conceptual point of view there also have to be musical merits. They are, luckily, abundant but there are also some less attractive features. Michael Schønwandt is, as Bill Kenny also pointed out in his review, the only Danish conductor to have appeared at Bayreuth and he knows his Wagner. There isn’t a tempo that I would question and his reading is very much kept together organically as one piece. The playing of the Royal Danish Orchestra is also first class, impressively so considering that these are live recordings.

Among the soloists there are some tremendously fine achievements. Johan Reuter as the young Wotan in Das Rheingold is vigorous and steady of tone, while James Johnson as the mature and ageing Wotan/Wanderer in the two following parts is admirably detailed and expressive in these demanding roles. Once or twice he overtaxes his voice but generally this is a superb portrait and in Siegfried his Wanderer is charmingly relaxed and humorous. Sten Byriel as the malevolent Alberich is also a splendid singing-actor and Stephen Milling, singing Fasolt’s role in Das Rheingold with melting bel canto tone, is a formidably nasty Hunding in Die Walküre. He is certainly one of the great present-day basses.

I found Stig Andersen’s Siegfried a bit uneven when I reviewed the Amsterdam Götterdämmerung on CD a while ago. On the other hand I admired his willingness to soften his voice and find nuances that too often elude Heldentenöre. Here he sings both Siegfrieds in addition to Siegmund and his is one of the liveliest and most likeable of interpretations of these taxing roles. Even though his tone can be strained and a bit dryish he sings with great attention to the words. As the mean and abominable Mime Bengt-Ola Morgny makes a memorably vivid portrait – on a par with the best I have seen – but his voice is today a far cry from what it once was. Both Christian Christiansen and Peter Klaveness create frightening characters of Fafner and Hagen. Guido Paevatalu, a mainstay at the Royal Danish Opera, is a lively play-boy type Gunther and his voice is still in good shape.

On the distaff side Iréne Theorin is so touchingly human a Brünnhilde that one forgets she is the daughter of a god. This is plainly the cosiest and warmest reading of the role I have encountered and she is a glorious singer. Today she is Bayreuth’s Isolde and she certainly has the stamina for that role too. At times she has a slight beat in the voice but when she lets loose at the climaxes she is brilliant. Gitta-Maria Sjöberg, whose recital disc with Verdi and Puccini arias I made a Recording of the Month less than a year ago (see review), has all the lyrical beauty and warmth one wants from Sieglinde. Du bist der Lenz has rarely been so gloriously sung. There are splendid contributions from Susanne Resmark (Erda and 1st Norn) and Randi Stene – a noble but grieved Fricka with Hilary Clinton looks. Ylva Kihlberg in several guises, not least her alluring Gutrune, should also be mentioned, and Gisela Stille is a deliciously twittering Woodbird.

While there may be other DVD Rings that are more consistently well sung, notably Barenboim-Kupfer’s Bayreuth set, this Copenhagen Schønwandt-Holten production is certainly wholly engrossing, fresh and perspective-building with deeply involving acting and several vocal achievements that compete with the best.

Göran Forsling

Given the spread of feminist literature on opera, and of feminist opera productions, it was probably only a matter of time before someone tackled Wagner’s Ring Cycle from a feminist point of view.

And yet on second thoughts, Kasper Bech Holten’s production of the Ring from the Royal Danish Opera, newly released on DVD in individual instalments after a complete release last year, seems incredibly daring and controversial. Though Wagner’s women are obviously complex and important components of his music dramas, to present the composer’s biggest project from the point of view of a woman requires a stretch of the imagination. Traditionally, Wagner has been seen as the most masculine of composers, metaphorically ‘killing off’ his women by submerging them with his masculine orchestra, sacrificing his women to redeem the male characters’ sexuality. More specifically, the Ring is usually portrayed as the story of Wotan, father of the gods; even in Götterdämmerung, when he’s no longer present in the story, his music continues to linger and dominate.

But not in Holten’s concept. Until the final scene, the cycle is staged as a flashback. At the start of Rheingold, Brünnhilde is seen tiptoeing through a dark attic by candlelight. According to the onscreen description of her actions, she has just betrayed her lover, Siegfried, and is in the attic to leaf through the photograph albums and discover the truth behind her family and her past, to help understand how she became the person she is now.

We’re then taken back to the Rhinemaidens’ scene. Kasper sets the cycle in the twentieth century, starting in the 1920s and moving on a generation for each opera so that the gods’ family tree is explored right back to its origins. The Maidens are flappers, and the gold is represented by a naked male youth swimming around in a fish tank. When Alberich steals the gold, he rips out the boy’s heart, and the purity of the ‘gold’ is ‘tarnished’ forever. The decadence of this period is ideal for the arrogance of Wotan in Rheingold and indeed the general atmosphere of self-indulgence. The scenes between the gods take place in the settlement of some kind of archaeological dig, a reference to the invasion of Tutankhamen’s tomb in the 1920s. With its gripping Personenregie, the production is filmed cinematically, and moments such as Wotan’s theft of the gold from Alberich in a torture chamber are intensely dark in conception.

Less convincing are Holten’s ambiguously-motivated impositions on the text. Why does Wotan kill Loge at the end of Rheingold? Why does Hagen kill Alberich? It’s one thing to add the prologue with Brünnhilde in the attic, but quite another to change the story completely. I was less than enchanted with the staging of the first act of Walküre, where Hunding’s hut is a rather twee little house that revolves with Siegmund and Sieglindeas they go out into the garden. The feminist aspect of the production takes an eccentric direction when it’s Sieglinde rather than Siegmund who removes Notung from the tree, thereby explicitly contradicting the text when Siegmund says that he is freeing the sword.

We’re now in the Cold War of the 1950s, when everything has gone stale, and the ambience of a long, silent wait suits the style of monologue found in the second and third acts rather well. The feminist reading works better with Brünnhilde’s intervention at the close of the act, and the intensity between her and Wotan in the third act highlights her Electra complex; the moment when Wotan removes Brünnhilde’s wings and takes away her freedom is chilling.

The Year of Love, 1968, provides the setting for Holten’s Siegfried. The idea here is to show Siegfried as a young man who’s part of a new generation that rejects the controlling power of its forebears and instead impose its own beautiful dreams on the world. But of course, such dreams are flawed and naive, and Holten’s nightmare vision ensures that we can see the weakness that lies behind Siegfried’s strength. The claustrophobia of Mime’s household is too much for him, and his need to break free is inexorable.

This gives way to a modern scene of corruption in Götterdämmerung, where the Gibichungs dwell in moral bankruptcy. One really does feel that the world is bound to collapse with such sinister figures in charge, and Holten makes allusions to the atrocities in Rwanda and Bosnia to heighten the atmosphere. Another imposition on the text made in the final opera is that Brünnhilde is pregnant by Siegfried, in direct contradiction to Wagner’s scheme. At the close, Brünnhilde is still in the attic and sets fire to all the diaries and photographs, before emerging during the final minute with a baby in her arms, the rising sun behind her symbolising the dawning of a new day on Brünnhilde’s life, rather than the destruction of the gods. Hagen, meanwhile, tries to steal back the gold when he makes his last-minute appearance, but it causes his arm to set on fire.

Though the Ring is always an invitation for spectacle, I can’t think of a more jaw-dropping staging of the piece on DVD. The sets are beyond lavish, with so many walls and winches and rooms and costumes and special effects that it’s rather like watching a high-quality, long-running BBC drama. Acting takes precedence always, and even where Holten changes the story in ways that don’t appeal or make sense (to me, at least), it’s impossible to resist the vitality of his direction.

I confess that my reaction to the musical aspect to this Ring is slightly more muted, much to my surprise. Claims that this was the best-sung Ring on film are unfounded, in my view, because the performance is both strengthened and weakened by having a cast plucked largely from the opera company’s ensemble. There are indeed some magnificent performances here, notably Stig Andersen’s almost impeccable Siegmund and Siegfried (undoubtedly the best of recent interpreters) and Iréne Theorin’s strong but feminine Brünnhilde. From both of them we get an unstinting level of emotion, expressivity and vocal beauty.

On the other hand, Gitta-Maria Sjöberg’s Sieglinde seems very limited compared to Waltraud Meier’s in other productions, while Peter Klaveness’ Hagen comes nowhere near to Sir John Tomlinson’s achievements in the role. Both act well but both sound provincial. Stephen Milling’s Fasolt is excellent, and both James Johnson and Johan Reuter are in fine form as Wotan, but many of the smaller roles are adequately sung rather than anything more. Michael Schonwandt’s conducting and the playing of the Royal Danish Orchestra are mostly very good and sometimes exciting, but I similarly have to temper the notion that the reading is special; to my ears, it’s a well-executed conventional account.

Instead, the stars are set and costume designers Marie i Dali and Steffen Aarfind, lighting designer Jesper Kongshaug and director Holten. To me, this Ring is unmissable for anyone with an interest in the piece, since it’s great to watch and has many arresting statements to say about the text, but those wanting higher musical standards will probably want to keep classic accounts by other conductors close at hand too.

Dominic McHugh | 22 July 2009

In a discussion with the opera enthusiast Queen Margrethe II of Denmark included on one of the Walküre DVDs, the director of the Copenhagen Ring, Kasper Bech Holten, reveals that its staging will not be repeated. So this intelligently filmed version, made live in May 2006, represents an enduring record of its remarkable achievement. Conducted with distinction by Michael Schønwandt, never less than finely sung and often outstandingly so, and acted with comprehensive commitment and insight, this landmark in Denmark’s operatic life—it was Copenhagen’s first Ring since 1912—will surely appeal widely in this format.

The production itself, naturally, has its controversial elements—any Ring of conviction by a contemporary director is bound to have. But while individual moments may seem perverse and are likely to provoke more than they persuade, and even the overall thesis has a modish tinge to it, the consistency with which the enterprise is carried through, together with the obvious thoughtfulness of the result, both fascinate.

The packaging is generally good, though Stewart Spencer’s English surtitles have been misattributed to Lionel Salter. As Holten explains in one of his booklet notes, this is essentially Brünnhilde’s Ring. The cycle opens with her searching Valhalla’s archive of documents and trophies for clues as to how things came to end up as they have, seen from her position near the end of Götterdämmerung. The very final image finds her still alive, having escaped the conflagration, and holding a newborn baby—Siegfried’s child—in her arms. Given a certain feminist outlook to the cycle as a whole—in Die Walküre, it is Sieglinde rather than Siegmund who pulls the sword from the tree—it’s presumably a girl.

Even if at first sight there’s a hint of the fashionable about this, the seriousness with which the female characters’ views are represented throughout adds to the cycle’s rich complex of meanings—certainly for a male viewer. That all of the singers have clearly understood Holten’s intentions and backed them to the hilt is also abundantly evident.

Some of Holten’s rewrites are more contentious, not only because they contradict Wagner, or at least add a heavy gloss to his original, but also because they limit rather than expand on what his work can signify. Wotan killing Loge with his spear at the end of Rheingold is one example, partly because it’s nonsensical, but also because it closes off the notion of the fire god abandoning his divine colleagues to become a freer agent. Hagen killing Alberich at the end of their scene in Götterdämmerung is another, because he’s the one major character whose fate is not clearly finished. Arguably, he’s a survivor of the catastrophe, with potentially further havoc to wreak. Maybe his possible continuance would have jarred with Holten’s optimistic mother-and-child end-image. If so, Wagner’s nagging doubt is surely preferable in its ambiguity.

Holten’s is a time-conscious production, with the characters visibly ageing between the first three operas. Johan Reuter’s young and impulsive Wotan in Das Rheingold is even replaced by the older and marvellously sung version offered by James Johnson in the later operas. The period progresses from the 1930s for Rheingold to the Cold War for Walküre, the emblematic year 1968 for Siegfried and the 1990s for Götterdämmerung, where Hagen and his vassals echo the Serb nationalist warlord Arkan and his genocidal paramilitaries in the Bosnian conflict. Little of the resulting imagery jars seriously, though exactly who the sophisticated and exotically fur-clad Erda is in what looks like an upmarket Agatha Christie Rheingold setting (Murder on the Rhine Express?) remains inscrutable.

The orchestral playing is of a very high standard—only in the hugely demanding prelude to Act 3 of Siegfried are there noticeable moments of uncultivated string tone—and if Schønwandt’s conducting needs a more vivid sense of character in Rheingold, his fast-tempo realization works extremely well elsewhere. Vocally, the main players are formidable, with Iréne Theorin’s accurate and tireless Brünnhilde an even match for Stig Andersen’s genuine Heldentenor contributions, which offer a sentient masculinity for Siegmund and a comprehensively commanding and physically youthful (except maybe in close-up) Siegfried. But he certainly looks nothing like 56, which was his actual age at the time, and his acting is as finely wrought as his singing. The Fricka, Loge, Alberich, Mime, Sieglinde, Hunding, Gunther and Gutrune would grace any production. Peter Klaveness does not supply an ideal bass gravitas for Hagen but he’s quite the nastiest exponent of the role one could encounter. This is a wonderful Ring to watch as well as to listen to, a must-have for Wagnerians anywhere.

GEORGE HALL