Der Ring des Nibelungen

Whether by luck or foresight, the decision to hire French director Patrice Chéreau was among the most important and courageous of Wolfgang Wagner´s entire tenure at the Bayreuth Festival. Not that Patrice Chéreau by any means was the Festival´s first choice to stage this Centenary Ring – The Nibelungen Ring marking the 100th year of the world premiere performance of the tetralogy in Bayreuth, as it seems among others Peter Stein and Ingmar Bergman declined offers.

Ultimately, French conductor and avant-garde champion Pierre Boulez brought in 31-year old French actor and theatre director Patrice Chéreau on short notice. He did not know Wagner and had previously only staged two operas, by Offenbach and Rossini. The rest, as they say, is history:

Together Patrice Chéreau and Pierre Boulez created a Centenary Ring in the truest meaning of the word: Simply the finest Nibelungen Ring production in the Centenary history of the work. Even after more than 30 years the power and freshness of this staging is virtually undiminished. As directorial concept and execution it remains unsurpassed, the closest competition, at least on DVD, being Harry Kupfer and Daniel Barenboim´s later Bayreuth Ring.

This Centenary Ring created one of the biggest scandals in the history of the Bayreuth Festival at the 1976 premiere, getting almost booed off stage with tumultous audience protests. The orchestra threatened to go on strike as well, disagreeing with Pierre Boulez´ interpretation of the score, officially complaining to Wolfgang Wagner asking to be allowed to play as they used to (read: Loud as opposed to Boulez´ transparent sound).

Time apparently changes everything: At the last performances in 1980, this Ring was hailed as a masterpiece with unprecedented hour-long standing ovations.

Whether one approves of Patrice Chéreau´s concept or not, one thing remains: In terms of influence in music theater, this Nibelungen Ring is probably the most significant operatic staging in history. To say that it revolutionized staging paradigms, especially in Wagner, for once would almost be an understatement.

What did Patrice Chéreau do that was so special? Something rather simple, in fact: He made the singers act, he brought genuine theatrical drama to the stage, something entirely unusual around that time. To appreciate the difference one just have to take a look at the preceding 1974 Wolfgang Wagner Ring in Bayreuth – small wonder, the audiences were shocked.

While the opera forays of many film directors have been of varied (read: limited) success, Patrice Chéreau is probably the exception that made many of his later film director colleagues attempt opera in the first place.

First of all, Patrice Chéreau´s trademark is the superb individual direction of the singers and an interpretation based on an extraordinarily detailed study of the text. He simply stages what is in the text (as he sees it, admittedly). Combined with his ability to bring alive the interpersonal drama to an extent I have not yet encountered in any other opera director. The interpersonal drama, such as in Walküre, is among the most compelling things ever to have be performed on an opera stage. Secondly, Chéreau just has plain sense of the theatre, combined with the usual French aesthetism.

Debated like few other stagings, some critics labelled this a Marxist Ring, others a Socialist Ring, while others again saw it as an extension of Shaw’s The Perfect Wagnerite. Patrice Chéreau himself was ambiguous in his comments, not committing himself to one singular interpretation (see his comments below under the individual operas). In any case, the interpretation of any staging ultimately lies with the spectactor.

Personally, I see Chéreau´s Ring as a parable of the 19th century Industrial Revolution and how it has corrupted society. Basically, this Ring begins around the time of it´s composition (1850-70) which does coincide with the Industrial revolution. In a Rheingold set around 1850-60, we see the Old World capitalist Wotan clash with the New World Capitalist Alberich. In Siegfried, the Industrial revolution is at it´s height, facilitating the forging of Nothung and in the cold and lifeless Götterdämmerung of the 1920´s we see the consequences of the industrialized society. Anticapitalistic or just the price of simple greed? Who knows? Patrice Chéreau will not tell. Whether Socialist or Marxist, I will leave others to argue.

Richard Peduzzi, later long-time collaborator of Chéreau was responsible for the sets. Open spaces, tied within the timeframe of the Industrial Revolution – brick walls and giant cogwheels spanning the side of the stage throughout the tetralogy.

The acting is uniformly excellent over the entire line. As pure vocal performances, few of the singers would be judged truly excellent by CD-comparison standards, but in the theater it was a virtually unbeatable cast, with only one (unfortunately major) exception: Siegfried.

Originally, this production was not conceived with television in mind, however these DVDs (as always from Bayreuth) were recorded in front of an empty auditorium in 1980 after Chéreau apparently made some adaptations for television. Video director Brian Large artificially inserted elements of smoke as well as advanced camera shifts during the scene changes.

Pierre Boulez provided a fast-paced, detailed and transparent reading, as such of high quality. However I ultimately feel he reduced the orchestra to simply accompany Patrice Chéreau´s staging (to be discussed in detail below).

An entire DVD (part of some box sets of this Nibelungen Ring) is devoted to the creation of this Ring.

This is not a so-called traditional Ring, of which the Metropolitan Opera Ring is the only available choice on the DVD market. In the overall “ranking” of Nibelungen Rings on DVD, I would place this Centenary Ring second only to Kupfer/Barenboim´s 1991 Bayreuth version, mostly due to Barenboim´s superior conducting and the superior casting of several of the leads (Siegfried, Wotan). Reviews of all seven available Nibelungen Ring versions on DVD may be found here.

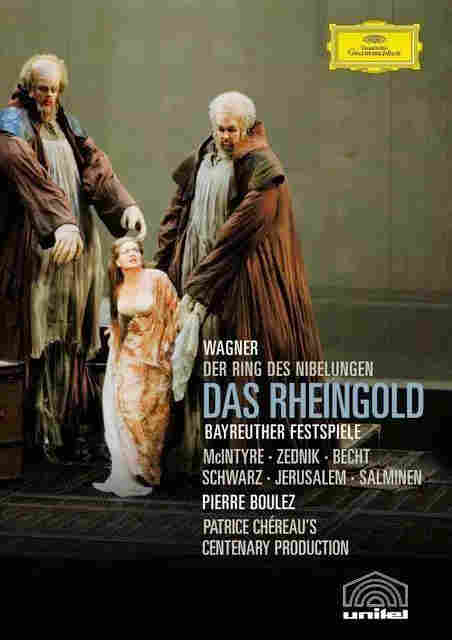

The individual operas – Rheingold

In the beginning we see a post-industrial concrete water-dam. The Rhinemaidens (1890´s can-can dancers? Prostitutes?) lure Alberich. The Gods come with 18th century dress and powdered wigs – representing the world in decay? Standing before a Valhalla construction of pillars but otherwise unanchored in time, though is seems already in the process of decay.

Moving down stairs anchored to brick walls as typically seen in the first industrial factories we arrive in Nibelheim. The Nibelungens are an amorphous mass (the rising working class?) slaving for the modern capitalist and factory owner Alberich (for once not portrayed like a complete idiot) fighting the ruthless old-world aristocracy in the shape of Wotan. A true danse macabre is seen at the end of the Rheingold, while Loge pulls the curtain.

In brief, it works more than well. The epic elements are expressed convincingly: The looming, threatening Valhalla, the eerie dam. Very impressively, convincing solutions has been found to stage several of the treacherous elements, such as The Rhinegold: Simply portrayed as glittering gold hidden under the dam; The dragon and the frog: No serious attempts are made to hide the transformation from Alberich into either, which oddly works rather well; Valhalla: An undefined building exterior looming over the stage.

Donald McIntyre´s Wotan is competent, though a tad passive and dry. He commands the stage convincingly as the aged, disillusioned patriach. He doesn´t have the legato-lines and interpretatory depth of James Morris, nor the compelling energy of John Tomlinson, his most obvious competitors on DVD. Nevertheless, his performance is rather fine and fits well within Chéreau´s concept. Accompanied by Hermann Becht´s equally dry-voiced Alberich, Heinz Zednik´s wonderfully energetic and sly Loge and Hanna Schwarz´ virtually perfect Fricka.

Patrice Chéreau: At the beginning of Rheingold, there is this object on stage which could perhaps be a dam but which could also be many other things. It is a menacing construction, a theatrical machine to produce a river, and an allegorical shape which today generates energy. It is perhaps a mythological presence, the mythology of our time.

One is supposed to portray Valhalla – but at the same time such a portrayal is impossible….What is needed is a Valhalla which leaves some doubt as to its exact concrete form, whilst at the same time signifying the material expression of power – the ideology of power..

[On Nibelheim] Violence is also an ingredient of mythology and it is impossible to portray on stage so many struggles – for dominance and for existence itself – so much pressure for change, and so much raw energy without including violence. Yes, the Ring is violent and cruel. Wotan is brutal and unjust, like Lear disowning Cordelia.

[On the Gods ascent to Valhalla]: The heavy, hopeless bitterness which appears with the curse motif and Fasolt´s death and which descends on the gods like the sickly mists of old age…For me this is the dance of death of medieval allegories..It all seems like a defiant flight into the future..Nothing is going right any more, but never mind, let us enter Valhalla all the same – a solution will be found later.

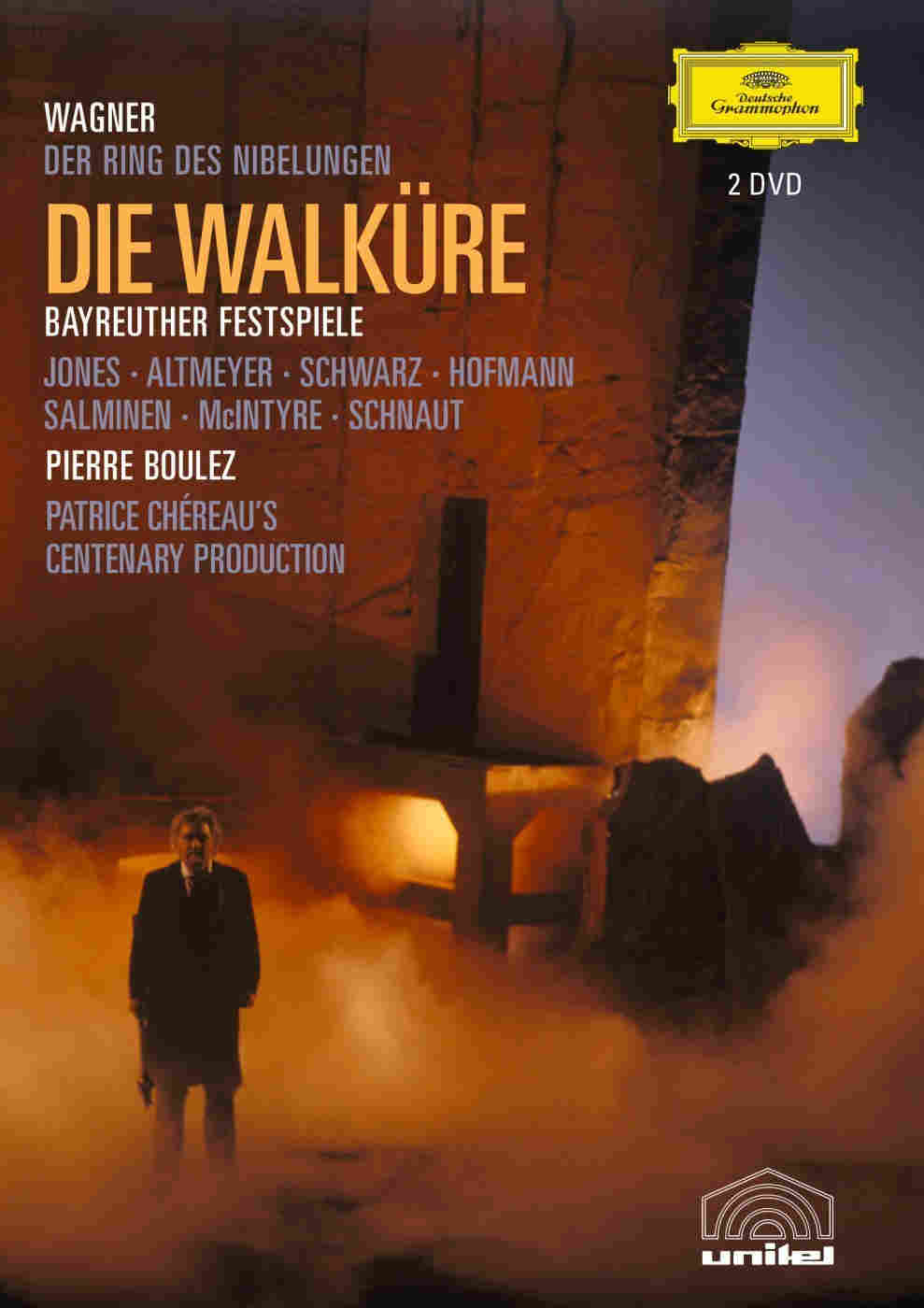

The individual operas – Walküre

Siegmund, the free peasant, arrives at the home of the wealthy land-owner Hunding. Or is he something else entirely? Clearly Siegmund, this genuine romantic hero does not know how to maneuvre in this world of capitalism and intrigue. Neither does his son, as it turns out in Götterdämmerung. Hunding does not arrive alone, but is accompanied by a group of men, in front of which the Walküre Act 1 chamber-drama is played out. Most importantly where most Walküre´s fail, this one succeeds: The drama is simply compelling.

Ideally Patrice Chéreau would have had a more compelling Wotan than Donald McIntyre to pull off the rest of the opera. Though by all standards McIntyre is more than competent, the drama involving Wotan (basically the rest of Walküre) never takes off to the same level as between Siegmund and Sieglinde. He commands the stage, but is relatively dry and monodimensional in vocal colouring as well as in characterization. Especially compared to his radiant daughter (Gwyneth Jones) and his stylish wife (Hanna Schwarz). Which is one reason why the “leb wohl” never truly takes off. The other reason is Pierre Boulez´ distinctly undramatic, uncontrapunctual reading (to be discussed in detail below).

To stage the second act in an unspecific room of Valhalla with a pendulum swaying in the middle almost approaches that of a genius. This is exactly what Wotan´s monologue is: The pendulum around which the Ring sways. Which suddenly stops dead right in the middle of Wotan´s monolong. Das ende. Indeed.

Most fittingly, the Walküre rock is a ruin – a remnant of past glory. The Wotan of The Old World desperately trying to maintain his empire..

The chemistry between Peter Hofmann and Jeannine Altmeyer is simply unsurpassed. On pure vocal terms neither may perhaps take place among the greatest in history, but when the intensity is like this, I honestly don´t even notice it, much less care about it. The most convincing Walküre Act 1 on DVD. Siegmund´s farewell to Sieglinde and his death is almost unbearably moving. Not to forget the young Matti Salminen as an excellent villainous Hunding.

Gwyneth Jones´ Brünnhilde is radiant. The wobble that later made her performances unlistenable was only incipient and though not always pretty in tone and not always on pitch, dramatically she has no real competition on DVD. As a “complete package” a better Brünnhilde is hard to find.

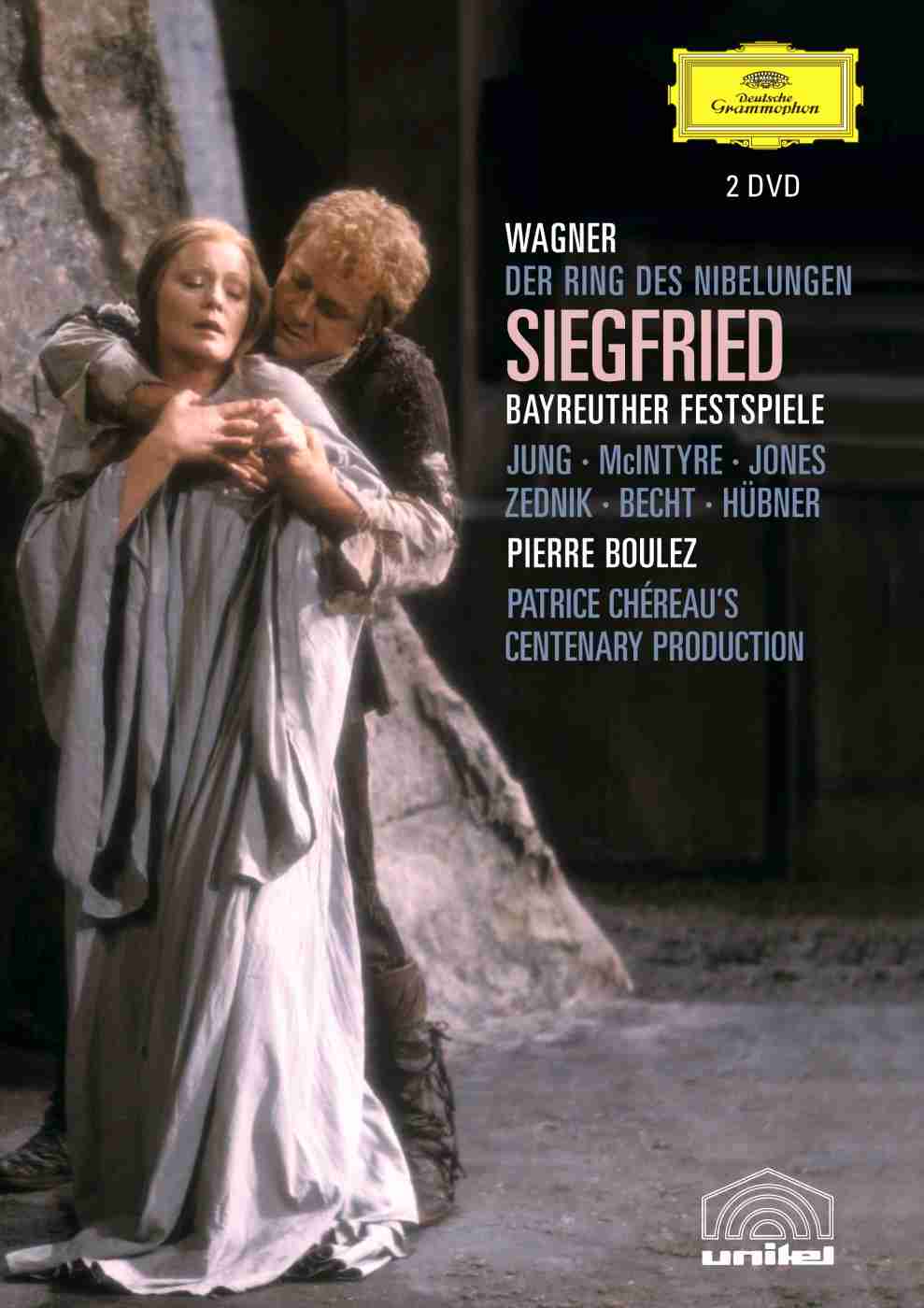

The individual operas – Siegfried

Mime and Siegfried lives amidst the cogwheels of industrialisation, conveniently next to a giant anvil. Though Nothung is not forged in the traditional manner, but rather melted in a proces made possible by the Industrial Revoluation. The gleaming Nibelungen gold is hidden among a forest of trees guarded by a giant toy-dragon wheeled in on a cartwright by stagehands. And someone conveniently has placed a bird-cage among the tree-tops. All ends on the crumbling ruins of the Walküre Rock.

Obviously Manfred Jung gives his best as Siegfried, and for this reason it seems unfair to go on at length about why exactly he doesn´t have what is required of this part. In fact his presence is a major draw-back to this Ring – vocally thin and physically unattractive as well as simply boring. A complete non-match for Gwyneth Jones´ Brünnhilde.

Donald McIntyre´s Wotan continues along the lines of Walküre and Rheingold – always the strongest in confrontations and declamations as opposed to the legato-lines dominating the Wanderer. On the other hand, his presence as A Man of The Past is rather convincing.

Heinz Zednik´s Mime is a perfect charicature of the underdog, with impeccably comic sense and timing.

Patrice Chéreau: Like it or not, there is an appalling cruelty in the scenes between Siegfried and Mime..Mime has to be both funny and tragic..

The scene with Fafner illustrates clearly that Siegfried´s freedom is only relative. The dragon warns him of the dangers of the world in which he lives, but the free man is not listening…And the central point of the tetralogy is precisely this: a hero has been created who would actually have had all the attributes of freedom, but that nobody remembered to tell him about them, and this man thus remains unaware and incomplete.

The individual operas – Götterdämmerung

Classic columns align the desolate world of the Gibichungen. They may be high-class and well-dressed – Gutrune in couture, Gunther in tuxedo, but all human values have gone. The industrial revolution as an inevitable, unstoppable process, which corrupts society? Or perhaps there are more layers..

Hagen in the crumbled suit is not a decisive factor – the wheels have been pre-programmed for this ending a long time ago. Siegfried, the naïve, obviously cannot manoeuvre in this world.

The images, needless to say, are spectacular. The interpersonal drama, unfortunately, relies mainly on Gwyneth Jones´ Brünnhilde, as neither Manfred Jung nor Fritz Hübner are very strong presences. And a bit more punch from Pierre Boulez would have been much appreciated.

Patrice Chéreau: To be precise, Götterdämmerung undoubtedly presents a world in which no values exist any more..The only possible refuge is in the past..It is hard to avoid seeing Götterdämmerung as a succession of rituals maintained at all costs, celebrated by people in search of a religion or a morality who may now carry on this cult in order to cover up the absence of any divinity.

By now Siegfried is a purely tragic figure…The draught of oblivion does not play a decisive part in this; the essential fact is that his own ego has never belonged to him, for he is programmed and deliberately programmed as if he were not programmed.

The beauty of the Ring is just as challenging today as when it was first performed, and what it has to say is still valid. The message remains aggressive and desperate, bitter and uncomfortable.

The singers

Generel comments: All singers look their parts and act well, a major contributory factor to the success of this Ring.

Wotan: Donald McIntyre´s Wotan is on the passive side. McIntyre´s tone is rather dry and he lacks both the interpretatory depth and smooth legato lines of James Morris as well as the sheer energy of John Tomlinson on competing DVDs. That said, he more than fits the bill and is an excellent dramatic actor, especially in the confrontational scenes.

Fricka: Hanna Schwarz must be close to the perfect Fricka: Beautiful tone, convincing presence.

Alberich: Hermann Becht´s voice is on the dry side and at points he almost retorts to yelling. His appearance on stage is convincing and, for once, not made ridiculous by the director.

Loge: Heinz Zednik´s Rheingold-Loge and Siegfried-Mime are both perfect examples of multifacetted engaged acting, superb comical timing and nuanced vocalism.

Fasolt: Excellent turnout for Matti Salminen.

Fafner: Ideally Fritz Hübner would have more sonorous ring to this deepest of deep parts.

Mime: Heinz Zednik´s Siegfried-Mime was a superb combination of excellent comic timing as well as plenty of character. Helmut Pampuch has considerably less to work with in the Rheingold-Mime, but made the most of it.

Erda: Ortrun Wenkel´s fine Erda would have be even finer with a more dramatically persuasive ring to it.

Sieglinde: Jeannine Altmeyer´s Sieglinde may be less than thrilling in pure vocal terms, however the on-stage chemistry with Peter Hoffman makes for a compelling performance. Futhermore she looks the part as few others.

Siegmund:Peter Hoffman may be cast as much for his looks than for his singing, but who cares? His singing is fine. Dramatically he is superb as the genuine tragic romantic hero. Best Siegmund on DVD. By far.

Hunding: Splendid performance from the young Matti Salminen

Brünnhilde: Gwyneth Jones´ theatrical radiance is simply unsurpassed. While incipient wobbly on her high notes, it does not seriously detract from her performance, though certain elements of strain are present and she is not always on pitch. She does, however, clearly have the vocal power to bring it off, in Götterdämmerung as well. Without doubt the best Brünnhilde on DVD and as a theatrical performer, one of the best of the century.

Siegfried: Manfred Jung´s underpowered and uninteresting Siegfried unfortunately is a major draw-back to this production, though he obviously makes an effort and gives his best.

Waltraute: Gwendolyn Killebrew´s dark mezzo and convincing dramatic presence is optimal for Waltraute.

Hagen: Fritz Hübner, not a genuine profundo (who is?) has trouble with the lowest notes and his presence is more that of a friendly competitor than the decisive menacing influence, which fits in well with Chéreau´s concept. Though one would wish Matti Salminen could have taken on Hagen in addition to his superb Hunding.

Gutrune: Wonderful performance from Jeannine Altmeyer.

Gunther: Franz Mazura both looks and sings on the dry side, not at all inappropriate for a Gunther.

The conductor and orchestra

Already in 1980 Pierre Boulez had conducted in Bayreuth for many years, since his 1966 debut with Parsifal (released on CD). Pierre Boulez is a masterful conductor in that he knows what he wants and how to execute it. Transparency is the operative word and in avant-garde works as well as in composers such as Debussy this leads to revelatory performances of immense clarity and entirely devoid of sentimentality.

This is essentially what Pierre Boulez brings to the Nibelungen Ring: A fast-paced, transparent, crystal-clear reading. However, while this approach adds to the understanding of the above-mentioned composers, in Wagner, in my opinion, it doesn´t add anything. Pierre Boulez essentially provides background music to Chéreau´s drama, where ideally the orchestra would have turned out an equally influential contribution.

In brief – The highlights and lowlights

The highlights: The theatricality and immensely compelling drama. The asthetic settings.

The lowlights: The casting of Siegfried.

The bottom line (scale of 1-5, 3=average)

The ratings are given in comparison to the other Ring DVDs available. As ever, the acting skills of the singers weigh in heavily.

Donald McIntyre (Wotan): 4

Hanna Schwarz (Fricka): 5

Hermann Becht (Alberich): 4

Heinz Zednik (Loge): 5

Matti Salminen (Fasolt): 5

Fritz Hübner (Fafner): 4

Heinz Zednik (Siegfried-Mime): 5

Helmut Pampuch (Rheingold-Mime): 4

Ortrun Wenkel (Erda): 3-4

Gwendolyn Killebrew (Waltraute): 5

Peter Hofmann (Siegmund): 5

Jeannine Altmeyer (Sieglinde): 4

Matti Salminen (Hunding): 5

Fritz Hübner (Hagen): 4

Manfred Jung (Siegfried): 2

Gwyneth Jones (Brünnhilde): 4

Jeannine Altmeyer (Gutrune): 5

Franz Mazura (Gunther): 3-4

Patice Chéreau´s staging: 5

Pierre Boulez: 4

Overall impression: 5

18 November 2008

It has been nearly thirty years since the centenary production of the Ring at Bayreuth, and the controversy and even scandal that it generated have long since faded into memory.

Videos of the production have been available for many years, and certain details—such as the hydroelectric dam which functions as the setting for the Rhinemaidens’ scenes in Das Rheingold and Götterdämmerung—have become almost legendary. Few, if any, of those who purchase this DVD set will be shocked by its contents, and there might be a tendency to regard this recent re-release as simply another re-packaging of familiar material. And yet it is this very familiarity that is so significant. If 1976 marks the appearance of the postmodern Ring, 2006 marks a different moment, in which post-modernism itself becomes historical.

In the most general sense, Chéreau’s production of the Ring can be called “neo-Shavian.” Like Bernard Shaw in The Perfect Wagnerite, Chéreau interprets the Ring not so much as an amalgam of Nordic mythology and medieval legend, but as a parable about industrialism. From the plush costumes of the gods in the second scene of Das Rheingold to the oversized iron flywheel that haunts the first act of Siegfried, Chéreau’s production is replete with references to the nineteenth century. These references operate powerfully on the contemporary viewer/listener. Unlike what we can call the “neo-realist” materials of the Otto Schenk/Günther Schneider-Siemssen production (which has dominated the stage at the Metropolitan for two decades), the detritus of nineteenth-century industrialism is still a part of our visual environment: the references therefore seem both historical and contemporary. Through his collage-like use of these visual materials Chéreau simultaneously locates the Ring in the nineteenth century and in our own time.

rheingold_boulez.jpgThis vision seems clearest in Das Rheingold. Chéreau takes full advantage of Wagner’s “anvil music” in the Nibelheim scene. Alberich’s minions look as if their bodies have been distorted by inhuman work in underground mines. The gods in the second and fourth scenes look not so much costumed as upholstered. If there is any problem with their appearance, it is that they look too decadent, too ripe for destruction. Only Donald McIntyre’s Wotan asserts the tragic dignity of the gods’ situation. Resisting the urge to let the voice fully bloom in the majestic music that opens the second scene (“Vollendet, das ewige Werk . . “), McIntyre presents a Wotan that—from his first appearance—is deeply conflicted. His lower range may lack some of James Morris’s authority, but McIntyre is a skillful singer and a consummate actor who fully inhabits his role. He carries Das Rheingold, and much of the rest of the Ring as well.

walkure_boulez.jpgThe first act of Die Walküre preserves the voice of Peter Hofmann (as Siegmund) before his rapid vocal decline. His undeniable beauty and physical vigor make him a charismatic presence, even if his singing lacks some of the nuance that other tenors have brought to the role. By casting Hunding as a wealthy nineteenth-century merchant, and having him enter with an intimidating group of retainers, Chéreau underscores the danger that Siegmund faces. Indeed, Matti Salminen’s Hunding is so menacing that it is hard to imagine that Siegmund—even with the help of his magic sword—will stand a chance against him. Hofmann also seems to be overshadowed by the Jeannine Altmeyer’s Sieglinde. Altmeyer’s voice is absolutely radiant, and she brings a sense of urgency to the role that at times borders on frenzy. In part because of her energy, the first act of Walküre is perhaps the most successful part of the Boulez/Chéreau Ring, in which musical and dramatic values completely support each other.

The production loses much of its clarity by the third act of Walküre. In the liner notes, the monolith that Chéreau uses for Brünnhilde’s rock is likened to one of the ruins that appear in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. But to this reviewer, its seems more closely linked to Böcklin’s famous “Isle of the Dead.” It seems disconnected from the quasi-industrial visual vocabulary that Chéreau uses for Rheingold: almost like a throwback to the pre-war designs of Emil Preetorius. Brünnhilde’s rock in Chéreau’s production is not merely a symbolic failure, but a dramatic one as well: flattening out the stage and restricting the possibilities for dramatic action. Chéreau seens to recover some of his ground in the first act of Siegfried, where Mime’s workshop gives ample opportunity to recoup the industrial imagery of Rheingold. The forging song, in which Siegfried uses a massive steam press to forge Nothung, is particularly effective. Chéreau also finds a good solution for the second-act dragon, which appears in this production as a clanking steel-plate behemoth rolled around by industrial workers. But like so many other directors, Chéreau seems befuddled by the “fairy-tale” aspects of the plot such as the “Forest Murmurs” and the Woodbird. Perhaps Chéreau lost confidence in his neo-Shavian interpretation of the Ring (this is hard to believe), or perhaps Wagner’s work is simply too diverse to be adequately encompassed by a single directorial idea. In any case, Chéreau’s hand seems to rest more lightly on the final two operas in Wagner’s tetralogy. Our attention is more keenly focused on the singers themselves, on whose abilities the success of the drama ultimately depends.

siegfried_boulez.jpgPerhaps the most welcome departure from the conventions of the Ring has to do with the presentation of Alberich. Unlike so many other interpreters of the role, Hermann Becht for the most part eschews the “Bayreuth bark,” and actually sings the role. His portrayal strengthens the drama immeasurably, highlighting all of those many places in the Ring in which we understand the gods and the Nibelungs as two aspects of the same psychic reality. In this production, more than any other, Wotan’s description of himself (in the Mime/Wanderer scene in the first act of Siegfried) as “Licht-Alberich” rings absolutely true. In the second act of Siegfried, Chéreau underscores the symmetry between Wotan and Alberich by costuming them in nearly identical ways. In the dim light that surrounds Fafner’s cave, the borders between gods, dwarves and men disappear.

Siegfried—perhaps the most challenging role in the entire tenor repertoire—is admirably sung by Manfred Jung. Jung brings to this role not only tremendous vocal stamina, but also keen intelligence. Shepherding his resources, he is able to master even the most difficult sections (such as the long narration immediately before his death in Götterdämmerung). Jung is not afraid to let Siegfried be unsympathetic and unheroic. He is not a particularly subtle singer, but for this interpretation of the role, he doesn’t need to be. Indeed, it is precisely because Jung creates such a brutal, coarse, unformed Siegfried in the third opera of the Ring that his transformation in Götterdämmerung is so powerful and compelling. In Jung’s interpretation, we understand Siegfried as a kind of elemental force similar to the Rheingold itself. He stands for human potential, morally neutral until transfigured by love.

gotterdammerung_boulez.jpgChéreau’s set for most of Götterdämmerung is sparse and not particularly compelling: here the Gibichung court is visually represented more through costuming than set design. In a wonderful touch, Gunther appears in a tuxedo. Hagen is in a rumpled business suit and Gutrune in a slinky white gown. Casting Jeannine Altmeyer again in this role has the effect of drawing attention to interesting symmetries and conventions in the Ring. When in the first act of Götterdämmerung she hands Siegfried a welcoming drink, we inevitably think of the refreshment that Altmeyer offered to another tenor in the first act of Die Walküre. As in the earlier opera, the beauty of Altmeyer’s singing has the effect of elevating the importance of the role that she portrays. This is particularly true because Fritz Hübner, the Hagen in this production, fails to dominate the opera. His acting is overshadowed by that of Franz Mazura (the Gunther of this Götterdämmerung), and his singing is rather monochromatic. This reviewer wishes that Boulez and Chéreau had brought back Matti Salminen (the Hunding of Die Walküre and the Fasolt of Rheingold) to sing this role (as he does in the Metropolitan opera video from the late 1980s).

Brünnhilde is portrayed by Gwyneth Jones, one of the most important Wagnerian sopranos of the twentieth century. Jones’s voice has a steely, hard-edged quality that foregrounds her occasional pitch problems and detracts, in many places, from a “purely musical” appreciation of Wagner’s work (as if such an appreciation were really possible!). Jones is least effective in those passages such as “Brünnhilde’s Awakening” in the last act of Siegfried (“Heil dir, Sonne”), in which her voice cannot completely flower into sonic beauty. But Jones is a consummate singing actor, and the video format, with its frequent close-ups, suits her well. Her performance in Götterdämmerung is absolutely magnificent. Here the edginess of her voice works for her rather than against her. She is a terrifying and formidable woman: Hagen’s call to the vassals—in which he describes approaching enemies and dire consequences for the Gibichung house—seems completely warranted in this production. And yet Jones is also intent on showing us Brünnhilde’s weakness and vulnerability. Her second-act entrance is particularly stunning. Bent over, white against the black formality of Gunther’s tuxedo, shrouded by her own hair, she embodies all the tragedy engendered by the lust for power and wealth.

Chéreau’s visual materials have become so famous that they have at least partially obscured the musical values that this production presents. As we might imagine, Boulez’s conducting stands in opposition to that of Levine’s which—at least to this reviewer—all too often lapses into self-indulgent languor. And yet many of Boulez’s tempi seem equally idiosyncratic. The Giants’ motive in the second scene of Das Rheingold, for instance, is played so quickly that it sounds almost like a limping can-can: Fafner and Fasolt do not lumber so much as shuffle their way into the presence of the gods. Perhaps the greatest disappointment—in musical terms—is Wotan’s Abschied. The magic fire motive sounds dry and mechanical: Loge’s mischievous energy reduced to the monotony of a typewriter. We may understand, and even sympathize with Boulez’s desire to bring more transparency to the score, and one is often grateful that he thins out the wash of orchestral sound that frequently overwhelms singers in other productions of Wagner’s works. The Boulez interpretation is always clear, and under his baton the singers are able to sing the most delicate piannissimi without danger of being lost. Donald McIntyre, in particular, uses this potential in order to bring a wonderful depth to his portrayal of Wotan. But the orchestral chestnuts of the Ring: the Ride of the Valkyries; Siegfried’s Rhine Journey; Siegfried’s Funderal Music, are likely to disappoint. In sections such as these, Boulez does not seem to fully trust the score. Unwilling either to press forward or to broaden the tempo. Boulez all too often settles into a tepid and lifeless interpretation. Great mid-century conductors such as Furtwängler and Stokowski were able to use tempo variation in order to convey the grand sweep of the music. Their interpretations are occasionally “sloppy,” but they always have a sense of direction and purpose. Boulez’s interpretation frequently loses this sense of direction. The supposed “clarity” of Boulez’s Ring; its stricter tempi and reduced orchestral sound, ironically have the effect of making the Ring less clear.

Boulez’s conducting is at its best in those sections that frequently present the most challenges to listeners (and perhaps to conductors as well): namely, those long discursive sections such as the Norns’ scene at the beginning of Götterdämmerung, or the two long Wotan/Brünnhilde duets in Die Walküre, in which Wagner’s Melos seems to press closest to recitative. Here Boulez’s metronomic approach to the score serves him well, lending the drama a sense of urgency and meaning. Boulez’s musical leadership, in short, has a defamiliarizing effect on the score: foregrounding certain motives, sections, and relationships awhile causing others to recede, forcing us to hear Wagner’s work in radically different ways.

Included along with the four operas of the cycle is a special documentary “The Making of the Ring,” that gives an account of the 1982 filming of the production recorded in this set of DVDs. The material in this hour-long documentary is not particularly well organized, but it includes some fascinating footage of earlier Bayreuth productions. One of the most interesting aspects of the documentary is the sections in which we see and hear Brian Large, the chief videographer for the Boulez/Chéreau Ring. In much of his other work, Large seems to take on a largely “transparent” role: letting in the television/video audience maintain the illusion, perhaps, that they are actually watching a stage performance of an opera. In this Boulez/Chérea Ring, however, Large takes on a more active role, not merely in the more-or less conventional camera work and fadeouts, but also in unusual effects such as those that we see during the “Descent to Nibelheim” music (described above), or “Siegfried’s Rhine Journey.” During this latter segment, se see Brünnhilde’s rock shrinking slowly against a black background, until it appears as nothing more than a glowing square in the middle of the screen. It is a simple, but highly effective idea, symbolizing both the physical and the psychic distance that is opening up between Siegfried and Brünnhilde. Large is clearly committed to the aesthetic values articulated by Chéreau and Boulez, and deserves credit as along with them as one of the co-interpreters of this production.

The flaws of the production are many, but it is deeply felt and passionately argued interpretation with tremendous significance. All serious Wagnerians should have access to this release. Although it documents a period, namely the late 1970s and 1980s, that has passed into history, it stands as a living testament to the power of reimagining Wagner’s works, and the imperative that we all share: to make them perpetually new.

Stephen Meyer | 03 Feb 2006

| DG, Philips | |

| DG |

Including the documentary Der Ring des Nibelungen – The Making Of

Also available as commercial audio release and live broadcast